Workers in the city of Los Angeles and in unincorporated areas of L.A. County got a bigger paycheck last month.

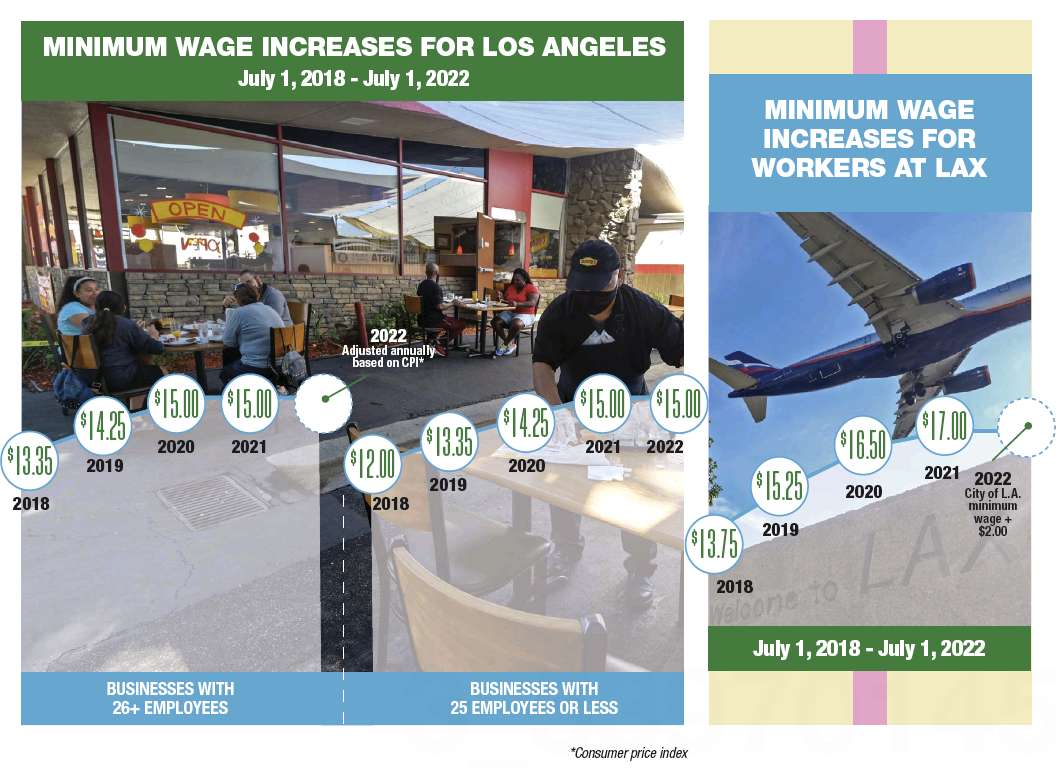

The pay boost kicked in July 1 when the minimum wage was raised to $15 for workers at businesses with 26 or more employees and $14.25 for those with 25 or fewer employees. That’s up from $14.25 and $13.35, respectively.

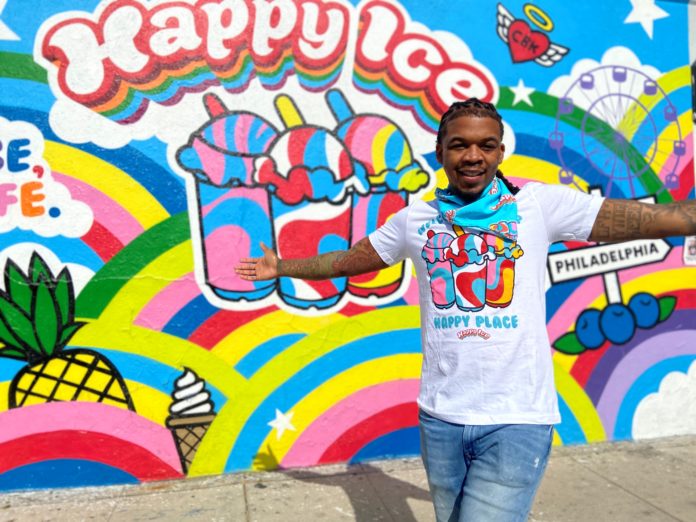

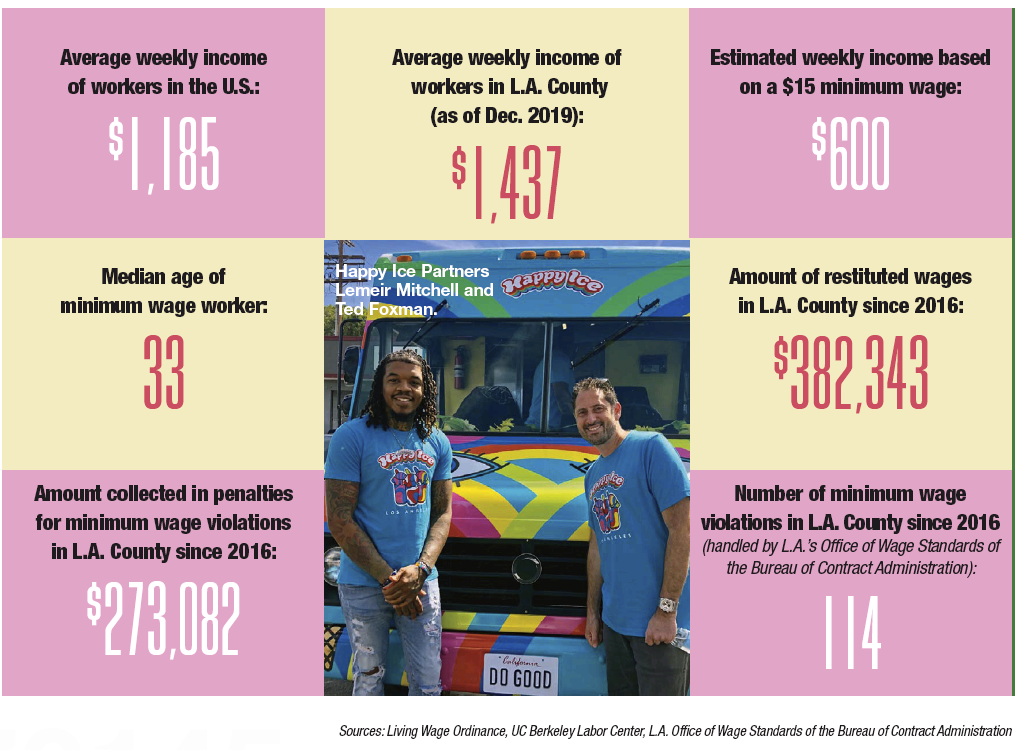

The increase went unnoticed at Happy Ice in Fairfax, which Lemeir Mitchell and his partner Ted Foxman opened in June after selling flavored ice desserts out of Happy Ice trucks for the last three years.

“We have already been paying everyone more than that,” Mitchel said. “People need to earn a living wage, so we are comfortable paying our staff that amount and more, so they can afford minimum of life’s essentials.”

Mitchell’s sentiment reflects that of L.A. city officials who passed an ordinance in 2016 that set in motion the first of five annual increases.

“Los Angeles is a low-wage city with a high cost of living,” city officials said at the time. “Without action to raise the wage floor, the problems caused by incomes that are inadequate to sustain working families will become more acute.”

“Contrary to popular perception,” the ordinance continued, “the large majority of affected workers are adults, with a median age of 33 (only 3% are teens). The proposed minimum wage increase will greatly benefit workers of color, who represent over 80% of affected workers.”

Similar increases were adopted by the cities of Malibu, Pasadena and Santa Monica, and supersede those implemented by the state at the beginning of the year — a rate of $13 per hour paid by employers with 26 or more employees and $12 per hour for those with 25 or less.

Los Angeles World Airports, the governing body for Los Angeles International and Van Nuys airports, went a step further with its Living Wage Ordinance, which guarantees an hourly rate of $16.50 for airport employees with benefits and $22.05 for those without.

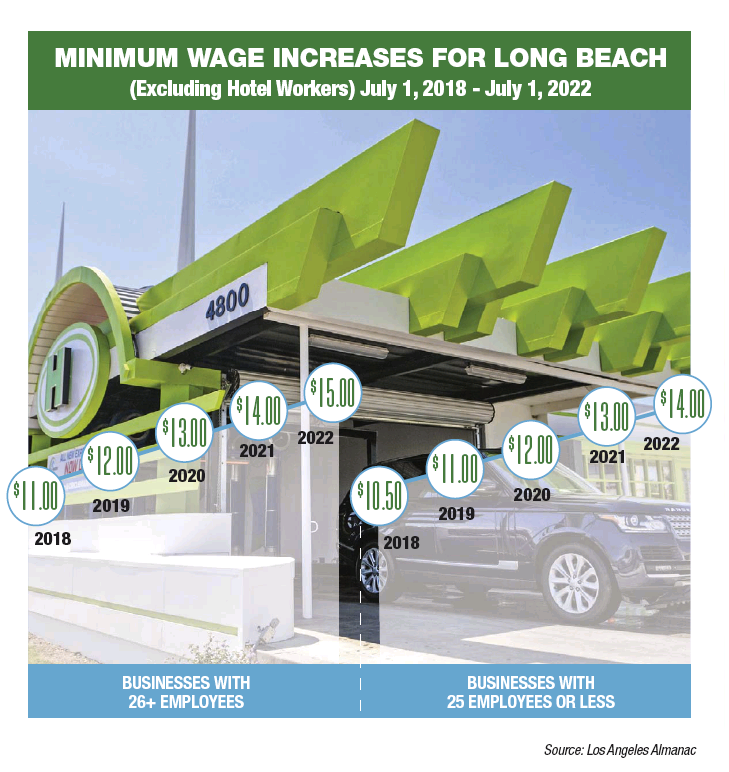

Other municipalities in the county, including Culver City and El Segundo, chose to follow the state regarding minimum wage increases for employees working within their jurisdictions and will fully catch up to L.A. by 2023.

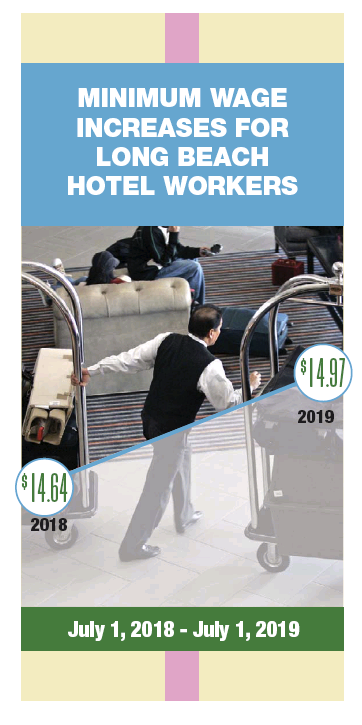

So did Long Beach, but it made an exception for its hotel and concessionaire workers who have been earning $14.97 and $14.72, respectively, since July 1, 2019.

At $15 an hour and working 40 hours a week, employees can earn $2,400 each month, or $600 a week. In December, L.A. County had 4.6 million workers who earned an average of $1,437 per week, slightly less than state’s average of $1,457, but well above national figure of $1,185.

However, about 34.5% of workers in the county earned less than $14.35 per hour, or less than $574 a week, according to a survey of 2017 employment data by UC Berkeley’s Labor Center.

The city of L.A.’s Office of Wage Standards of the Bureau of Contract Administration oversees enforcement of the ordinances. It has investigated more than 900 employers since 2016, nearly a quarter of them are from the restaurant industry.

The agency has closed 436 cases to date — 114 with violations — collected $273,082 in penalties and provided restitution of $382,343 in wages owed to 2,962 workers.

The legislation that set the state toward the $15 hourly rate by 2022 was enacted in 2016, well before the coronavirus pandemic decimated national and local employment rates and shuttered nonessential businesses in the state for nearly three months.

The California Chamber of Commerce urged Gov. Gavin Newsom to postpone the state’s next minimum wage increase, set to take effect on Jan. 1.

“In order to stimulate a recovery, the Legislature needs to refrain from imposing any new burdens on employers and proactively eliminate or suspend costs and burdens so that employers can reopen and rehire the millions of workers who have lost their jobs,” chamber Executive Vice President Jennifer Barrera wrote in a letter to Newsom.

“Sponsors of the 2016 legislation to raise the minimum wage (provided) the governor the option to postpone by a year any of the annual step increases in the event of a major economic recession or state budget crisis. … The criteria in the law for postponement fit the current conditions like a glove,” Barrera added.

Percentage of Low-Wage Work in California by County

| County | Percentage of Low-Wage Work |

|---|---|

| Merced | 46.6 |

| Lake, Mendocino | 46.3 |

| Tulare | 45.1 |

| Colusa, Glenn, Tehama, Trinity | 43.5 |

| Sutter, Yuba | 42.0 |

| Fresno | 41.7 |

| Kern | 41.7 |

| Riverside | 41.6 |

| Butte | 41.5 |

| Imperial | 40.5 |

| San Joaquin | 40.1 |

| Madera | 39.7 |

| San Bernardino | 39.4 |

| Kings | 38.7 |

| Humboldt | 38.6 |

| Monterey, San Benito | 38.6 |

| Shasta | 37.6 |

| Stanislaus | 36.9 |

| Santa Cruz | 36.6 |

| Alpine, Amador, Calaveras, Inyo, Mariposa, Mono, Tulumne | 36.0 |

| Santa Barbara | 35.9 |

| Del Norte, Lassen, Modoc, Plumas, Siskiyou | 34.7 |

| Los Angeles | 34.5 |

| Yolo | 34.3 |

| Ventura | 33.9 |

| San Luis Obispo | 32.3 |

| Placer | 31.7 |

| Orange | 31.3 |

| Solano | 30.4 |

| Sacramento | 29.9 |

| San Diego | 29.6 |

| El Dorado | 29.2 |

| Sonoma | 28.7 |

| Napa | 26.7 |

| Marin | 25.3 |

| Contra Costa | 24.5 |

| Alameda | 21.8 |

| San Mateo | 19.2 |

| Santa Clara | 18.3 |

| San Francisco | 16.5 |

| Nevada, Sierra | NA |

Source: UC Berkeley Labor Center analysis of IPUMS American Community Survey 2017