Contract negotiations are underway for workers at the Port of Los Angeles and the Port of Long Beach.

The talks between the Pacific Maritime Association, representing employers at 29 ports along the West Coast, and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, which represents 15,600 dockworkers at those ports, started last week.

The current contract expires July 1.

For shippers, the concern is that if talks bog down it could exacerbate the already fragile supply chains for companies that depend on the ports. For the union, the main issues are higher wages and automation that would eliminate jobs on the docks.

Both employers and workers begin the talks following a period of cooperation during the pandemic, according to PMA Chief Executive Jim McKenna.

“From a general perspective, I think the relationship between the two sides is very healthy,” McKenna said at a May 6 press conference. “We’re all focused on this contract.”

On the other side of the table, Willie Adams, president of the ILWU, wrote in an open letter that “automation poses a great national security risk as it places our ports at risk of being hacked.”

Contract negotiations between Pacific Maritime Association and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union kicked off last week in San Francisco and will likely stretch past July 1, the date the dockworkers’ collective bargaining agreement is set to expire.

“They always do,” PMA Chief Executive Jim McKenna said during a May 6 press conference with Port of Los Angeles Executive Director Gene Seroka. “I think everybody is optimistic going into this one that we’re going to get to where we need, and whether we go past July 1 or not is not the issue. It’s just we need to stay at the table and get an agreement without causing any further disruptions.”

For shippers, the concern is that if talks bog down, it could exacerbate the already fragile supply chains for companies that depend on the ports.

McKenna, whose organization represents interests of employers at 29 ports along the West Coast, noted that in 2002 the two sides signed a contract in October after a 10-day lockout that “took us three months to dig out from underneath.”

The 2008 agreement contained an automation clause that allowed employers to install some labor-saving equipment. McKenna said everyone thought it was “going to be tough to overcome,” but the new contract was ratified three weeks after the old one expired with “little to no disruption.”

He also mentioned the 2014 negotiations that took about 10 months to resolve. The ILWU at the time decided not to extend the 2008 contract past the July 1 deadline, which resulted in dockworker slowdowns, but also for retaliatory cutbacks on higher paying night and weekend shifts by the employers.

The current negotiations appear to be off to a better start.

“From a general perspective, I think the relationship between the two sides is very healthy,” McKenna said. “The pandemic and coming together and really working towards overcoming the obstacles … has solidified our ability to work together. (There will be) difficult issues to discuss, whether they’re hours, wages, working conditions, and there will be other topics, but I think we’re all focused on this contract. And like all the other contracts, it will have a start, it will have a finish, and whatever happens in the middle will be between the two sides.”

Union perspective

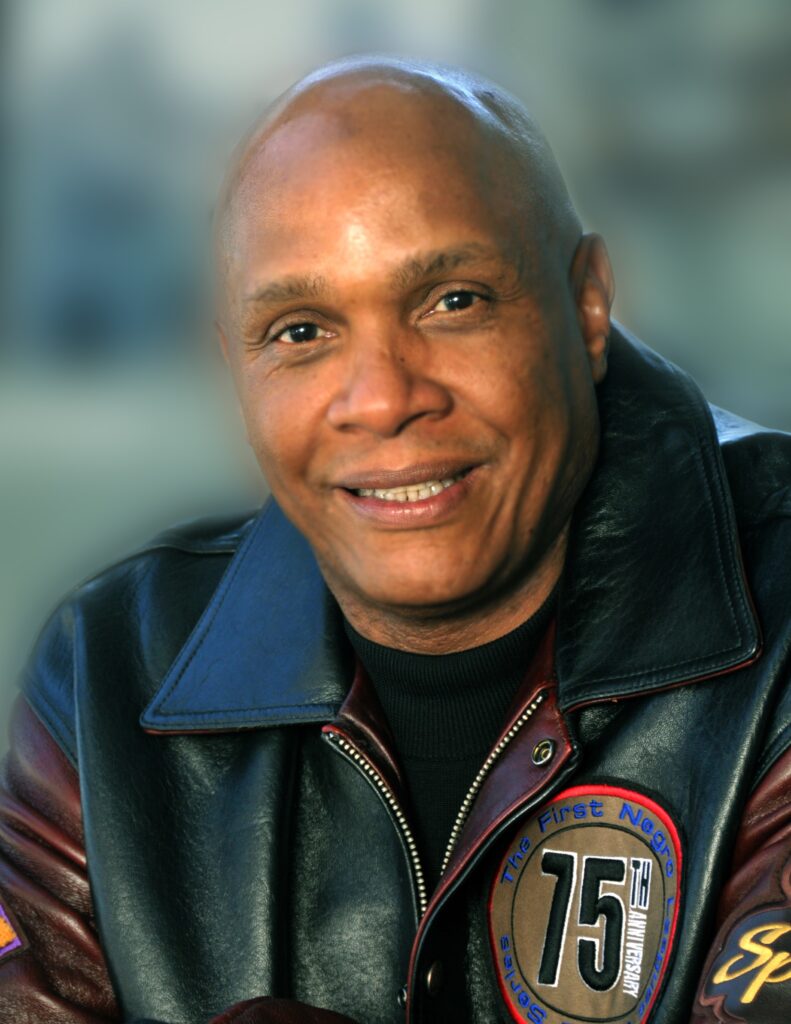

The same day McKenna chatted with the journalists and Seroka, Willie Adams, president of the ILWU, issued an open letter that summarized the challenges local dockworkers faced during the pandemic. The letter also hinted at what union’s potential asking points might be – namely, an objection to the spread of automation and an increase in wages.

“While the pandemic has underscored the significance of our ports to our economy and our day-to-day lives, it has also shined a light on the shadows of how our ports operate – exposing the fact that while the land on which they sit may be owned by the taxpaying public, a vast majority of our port terminals are leased out to the same foreign-owned billion-dollar shipping companies that gouged American businesses by charging them 10 times the usual shipping rates and have contributed toward the rise in inflation,” Adams wrote. “Some of these shipping companies are also attempting to automate the U.S. terminals they lease – using robots instead of American workers to operate the heavy equipment that moves cargo. Other ports have tried this and found that automation not only kills good jobs but does not move more cargo. In addition to a loss of jobs, automation poses a great national security risk as it places our ports at risk of being hacked as other automated ports have experienced. These attempts should be a concern for our nation as the intention behind them isn’t what’s best for America, but rather what’s best for foreign profits.”

Adams’ remarks follow a May 2 release of a PMA-sponsored report that lauded use of automation at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. TraPac Terminal and APM Terminals at the Port of Los Angeles, as well as Long Beach Container Terminal and Total Terminals International at the Port of Long Beach are planning to or have adopted automation in various degrees, while the remaining nine terminals at the San Pedro Bay port complex have not.

In the letter Adams also emphasized that previous negotiations “have made longshore jobs good blue-collar jobs.”

“We make no apologies for achieving wages that allow workers to provide for their families, have retirement and the health care these difficult and dangerous jobs require,” he wrote. “It’s our belief that the American Dream shouldn’t be reserved for CEOs and companies based overseas but should be within reach of the workers who are responsible for their employers’ success.”

Leverage

The bargaining agreement will cover more than 15,600 dockworkers at 29 ports, including thousands at the Port of Long Beach and Port of Los Angeles who are members of the ILWU Locals 13, 63 and 94. PMA meanwhile represents 70 ocean carriers and marine terminal operators along the West Coast, and its responsibilities go beyond contract negotiations.

“We hire, we fire, we discipline, we arbitrate work issues and disputes, we dispatch, we payroll and train the workforce,” McKenna said. “We also administer all benefits including health care, pension, vacations, 401(k)s. We basically represent the maritime industry in all aspects and dealings with all ILWU workers employed at the 29 West Coast (ports), the exception being direct supervision on the docks. However, if there is a problem on the docks, PMA is usually involved in the resolution.”

When asked if labor has more leverage in the current negotiations, considering their role as essential workers during the pandemic, McKenna agreed.

“Labor always has leverage – we’re a regulated monopoly,” he said. “The only people that do work in the 29 West Coast ports are ILWU members, so there’s always a lot of leverage on this contract, more cargo (or) less cargo. But I think now there’s probably leverage on both of us, with all of these ships that are at anchor. …

“And if China kicks loose and start sending those 500 ships that are sitting there back at us, we’re going to see a really big surge and we have to realize that and do what we can to get to the table (and) get a contract,” he added.

As the two sides prepared to push for their priorities, last month dockworkers at the Port of Los Angeles moved 891,582 containers, measured in 22-foot-equivalent units (TEUs), including 459,918 TEUs of imports, a 6.2% year-over-year dip. Exports declined 15% to 96,811 TEUs, while the volume of empty containers was also down 2.2% to 334,852 TEUs. Stats for the Port of Long beach were not available at press time.