Michael King knows a hit when he sees one. His TV syndication company picked up “Wheel of Fortune” for pennies and sold it to stations for a fortune. He followed that with distribution of “Oprah” and “Jeopardy.”

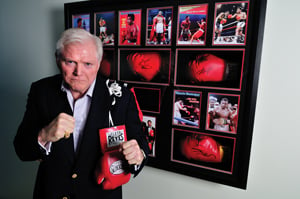

Decades later, King is now looking for his next knockout – and thinks he’s found it in the boxing ring. Next month, he will launch a professional boxing series at the Barker Hangar in Santa Monica. The plan is to promote the fights, sell tickets and score a major TV rights deal.

King, chief executive of upstart boxing promoter King Sports Worldwide of Brentwood, said the key to his company’s success will be minting new champs for the sport.

“Our goal is to create stars,” King, 66, said in an interview with the Business Journal. “Until I build another superstar like Sugar Ray Leonard or Oscar de la Hoya, the jury is out on whether I’ll succeed.”

The strategy has been in the works for a few years, but will kick into high gear April 16 with the first Santa Monica event, followed by at least three more bouts at the venue later this year. King hopes to sell those events to TV networks.

He’s hoping to tap into the billions of dollars spent on TV rights for the major sports, as seen in recent deals for Dodgers and Lakers games. Sports programming is particularly valuable these days to networks because people tend to watch live and are less likely to fast-forward through ads.

The biggest boxing matches currently air as one-off pay-per-view events on HBO or Showtime. There are also other fights on those channels and even on NBC and Fox cable channels. Smaller cards are also shown weekly for most of the year on ESPN’s “Friday Night Fights.” ESPN buys the rights to those events on the cheap, King said.

But he thinks boxing could command the mammoth paydays seen with the major sports, if it was presented in the right way to networks. That means serialized, high-end productions complete with storylines based on his stable of fighters – about 24 boxers from around the world he has signed.

Of course, he will still have to sell his pitch to the TV industry – certainly no easy task, especially given the well-established incumbents. Promoters such as de la Hoya’s Golden Boy Promotions of Los Angeles and Bob Arum’s Top Rank Boxing of Las Vegas already have deals with Showtime and HBO to show their fights.

The challenge is not only to compete for those time slots, but also to convince a network to buy unproven boxing programming, said Michael Rosenthal, an L.A. boxing writer and editor of the Ring magazine.

“It’s like any other TV show – it depends on if you can convince the network it can work,” Rosenthal said.

Training ground

King got started in the TV syndication business about 40 years ago when he went to work at the family firm in New Jersey after his father died. At the time, the company only sold reruns of “Little Rascals.”

He and his late brother Roger took the reins and built the company, King World Productions, into the biggest player in first-run syndication. That means licensing episodes to TV stations that want to supplement their independent programming or network shows.

King World had its major breakthrough in 1982, when the company paid Merv Griffin $50,000 for the rights to distribute “Wheel of Fortune,” followed soon after by a deal to sell “Jeopardy.” The company earned licensing fees from the shows.

The Kings, meanwhile, gained a reputation as two of the savviest salesmen in the TV industry and the company went public in 1984. The company struck gold again two years later with a deal to syndicate “The Oprah Winfrey Show” nationally. At the time, she was still hosting a local talk show in Chicago.

Those deals were the basis for a 1992 New York Times profile that called the Kings “by far the richest family in television.”

The brothers hit a payday again in 1999 when CBS acquired the business for $2.5 billion and merged it into its CBS Television Distribution division. The Kings together owned about 20 percent of King World at the time of the sale, according to reports.

Roger King stayed on to run the CBS division, until his death in 2007, while his brother took a more informal consulting role.

Michael King also dove into the sports business. His friend Ray Chambers, who made a fortune buying and selling the Avis rental car business, gave King the chance to buy a small stake in the New York Yankees, and New Jersey Devils and Nets.

The experience showed him how expensive it is to run those franchises. He’s fond of saying that even when the Yankees won a World Series and the Devils won a Stanley Cup in the same year, the teams still managed to lose money.

He sold his stake in the teams, but saw another option in boxing, in part because the events are cheaper to produce and TV sports rights were steadily climbing in value.

“When you look at television, this thing jumps off the table,” King said.

Stepping up

King grew up idolizing fighters such as Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, but wasn’t directly involved with boxing until 2008, when he opened a training facility in Carson called the Rock, catering to amateur fighters.

The plan was to take athletes who had competed in other sports such as football and train them to become Olympic fighters for the United States team – specifically heavyweight champions. It was an attempt to address a widely acknowledged problem in boxing.

“The joke is that the best American heavyweights are playing linebacker in the NFL,” Rosenthal said.

In 2009, King raised about $25 million in financing from wealthy contacts interested in boxing – he declined to give their names for this article. He outfitted the Carson facility with state-of-the-art equipment, brought on known trainers and staged hundreds of amateur bouts.

The facility had a measure of success. One of its trainees was Dominic Breazeale, a former quarterback at the University of Northern Colorado with no boxing experience. He qualified for the 2012 Summer Olympics in London as a superheavyweight. However, Breazeale lost in a preliminary match to a Russian fighter and the U.S. boxing team had perhaps its worst showing ever, winning no medals.

King had invested about $10 million into the Olympic training effort, but decided to shut it down around the time of the London games as he was disillusioned with the political workings of the U.S. Olympic boxing program. The facility is still open for use by the community, however.

King then decided to jump into the pros. His representatives scoured the globe for fighters. The promotion company’s stable now includes Mark Heffron, a middleweight fighter from the United Kingdom who has an undefeated professional record, and Chris Van Heerden, a welterweight from South Africa.

King signs his fighters to five-year contracts. He pays on a per-fight basis and also offers profit participation, he said. He acknowledged that his fighters aren’t widely known, but he said they will be once he throws his promotional muscle behind them.

He’s also hoping sponsors will step in to further build the profile of his fighters. That can be done, although it really depends on getting the right fighter, said Dean Baker, a manager and head of the boxing division in the London office of L.A. sports and entertainment marketing firm Wasserman Media Group.

Baker has recently made deals with Nike, Subway and Coca-Cola to sponsor his client, British boxer Anthony Ogogo. He said it comes down to presenting an athlete who has talent, looks and intelligence. Boxers don’t always have all three.

“The trick for me has been introducing my guys to the decision-makers of the brands,” he said. “Let them sit in a room for an hour and let the boxer do the talking.”

Baker works with Golden Boy to promote Ogogo’s fights, but said he welcomes the entrance of a new promoter looking to invigorate the sport.

King hopes to do just that. He wants to make this month’s event at the Barker a star-studded affair by inviting celebrities. Comedian and actor Kevin Pollak will MC the fight. He’s also inviting press to spread the word and, of course, TV network executives. He estimated that his first event at the Barker will cost about $400,000 to produce. The venue holds 3,000.

But his ambition is to make the sport into a far larger spectacle.

“There are things we can do traveling this around the world,” he said. “Imagine a worldwide broadcast from the top of the Burj Khalifa skyscraper in Dubai.”