When Raymond Novell moved to Monrovia as a child in 1947, he was just up the street from the Alta Dena Dairy, which had been founded not long before by three Stueve brothers. For the next 60 years, Novell’s life would be intertwined with the children of the brothers.

He attended kindergarten with two of those children, worked at the dairy’s drive-through outlets as a teenager and backpacked through Europe with one Stueve son. After Novell got his law degree, he began a long tenure as chief counsel for the company, which grew into one of the largest family-owned dairies in the country. One of the Stueve granddaughters even asked the longtime friend, affectionately known as “Ran,” to walk her down the aisle after her father died.

When it came time to manage the family’s wealth, of course they chose Novell for that important duty.

“He became one of the family,” said Jackie Arthur, one of the Stueve children, who has known Novell since they were in kindergarten. “He was someone who was a part of our lives.”

Today, the Stueve estate, the fruit of decades of hard work, is out of cash. It’s been drained, surviving members allege, by their trusted friend, who took at least $15 million. Some property remains in the estate that is worth millions, although estimates vary.

“We were always told that we had this estate plan, that we were going to be taken care of in our old age and have something left for the grandchildren,” said Judy Claverie, another of the Stueve children. “We were just shaken to our core to be told the money was gone. It was an eye-opening betrayal.”

The family removed Novell as trustee last year, and filed a lawsuit seeking to recover money and property. The suit accuses him of stealing the money, mostly through a series of loans to himself, his friends and his family.

“The family opened up their trusts and found a bunch of IOUs,” said Michael Meyer, the Stueves’ new trustee.

Novell’s attorney, Hugh Burns, denied the allegations. He said his client was an effective manager and pointed out that the family still has the real estate.

“They received millions of dollars of benefits the past eight years, and they haven’t received any payments since the new trustee took over,” he said. “All that was by the efforts of Mr. Novell.”

A phone number listed for Novell was disconnected, but in a declaration filed in Orange County Superior Court, he stated that the loans he made were not to himself, and for investment purposes only.

Andy Katzenstein, a partner in the Century City office of Proskauer Rose LLP who specializes in estate planning and litigation, agreed to review the case for the Business Journal. He said he had never come across similar allegations against an attorney.

“I’ve practiced for 28 years and I’ve never seen anything like this,” he said. “I’ve seen people take a loan here and there, and when they get caught they say, ‘Oh, my goodness,’ and put it back, but I’ve never seen one like this.”

Some family members are still living comfortably off savings, but others have faced hardship since the alleged problems were discovered a year ago. The 59-year-old Claverie, for example, has amassed $100,000 in debt in the past year, maxing out her credit cards and borrowing from friends to pay the mortgage on the Bradbury home she inherited from her parents. She is considering selling the property.

Missouri farmers

The Stueve brothers – Harold, Edgar and Elmer, all now dead – hailed from a Missouri farming family and were the eldest of 18 siblings. Equipped only with eighth-grade educations, each brother began working at the age of 12, boarding at neighboring farms and sending money back home. When they got old enough to strike out on their own, they moved west to California, picking their way across the country as migrant farmers.

“It was such a simple beginning,” said Jean Behrend, daughter of Edgar. “My dad, when he came out on the train, didn’t know how to order anything but beer.”

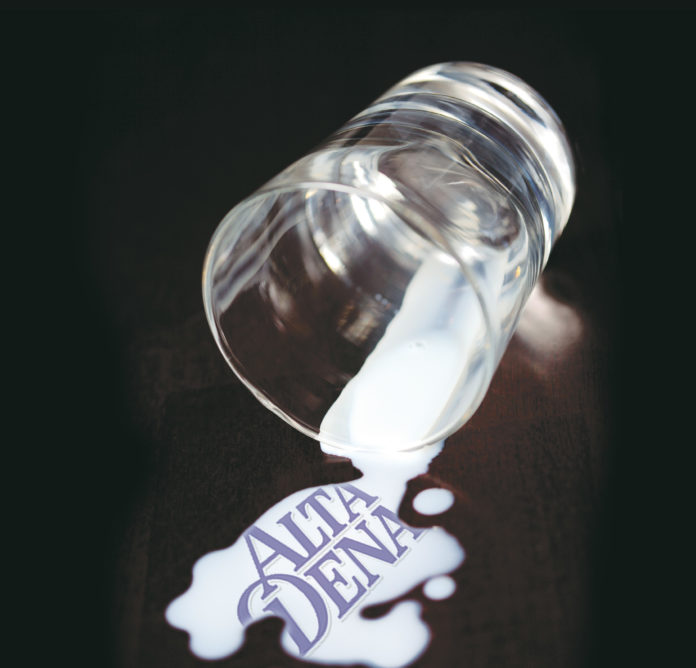

The brothers landed jobs working at Foothill Dairy in Azusa. Before long, they saved up and started their own dairy on four acres in Monrovia, with roughly 60 cows, two bulls and one milk truck. The Alta Dena name came from their first delivery route in 1945 in Altadena. In 1950, riding California’s postwar boom, the brothers bought 100 acres in Chino for a larger herd. About the same time, Alta Dena Dairy’s trademark drive-through stores began to appear.

“It was the time and place for Horatio Alger stories,” said daughter Arthur, who lives in Pacific Palisades. “Businesses started then and just went off. In-N-Out started around the same time. It was just a time of expansion and they rode that wave.”

Expansion was rapid, and by its height in the 1970s and ’80s, Alta Dena Dairy had about 17,000 head of cattle on six properties and employed nearly 70 family members. Unlike most dairies, the family kept all production in-house.

In 1989, the Stueves sold the retail side of the business and the Alta Dena name, which continues separately, but the family kept on farming and producing milk as Stueve Bros. That period was marred by the death of oldest brother Elmer in 1992 and controversy over its continued sale of raw milk amid a crackdown by health authorities. A legal defeat involving the alleged theft of trade secrets of a yogurt maker prompted Stueve Bros. to file for bankruptcy in the late 1990s.

Trust and trusts

The family dairy, which ceased operations last decade, emerged from bankruptcy within a year with land holdings valued up to $60 million, according to new trustee Meyer. In 2001, the two surviving brothers decided it was time to set up trusts to protect the family fortune. Most of their children would soon be reaching retirement age without a steady income.

To set up and manage the trusts, they tapped Novell, who was so concerned with preserving the family’s legacy that he was working on a book about them and had even bought artifacts from their old home in Missouri for a museum.

Edgar died in 2002 and his brother, Harold, four years later.

The setup was a typical one for individuals who want to avoid a capital gains tax.

Each family member’s interest in the business was placed into 16 charitable remainder unitrusts. Six CRUTs were established for the brothers and their wives, one for each of the brothers’ nine children and one for the divorced spouse of one of the children. The CRUTs were designed to make payments until the heirs’ deaths, after which the remainder would go toward charity. Novell was designated trustee.

At the start, cash continued to trickle in from a property that had been sold before the trusts were set up, and family members received regular payments. In 2004, Novell struck a deal to sell the family’s most valuable piece of real estate, a wholly owned 272-acre parcel in Chino, for $28.5 million to a developer looking to build homes.

But the market turned, the buyer defaulted and the sale fell apart. By September 2009, family members say Novell broke news that there wasn’t enough cash left to make payments.

Suspicious family members, who had become frustrated by what they perceived as a lack of transparency, asked Meyer, a friend, to look at their finances. They claim Novell had warned them not to share documents with others, citing a breach of confidentiality.

Meyer and another attorney, James Daily, reviewed the documents and concluded that Novell, with the aid of another attorney he had brought in, J. Wayne Allen, had been using the trusts as their personal bank account.

According to the lawsuit, they found dozens of loans, many of them never repaid, which they allege were made by Novell and Allen to themselves, their own family members and sham corporations they controlled. Novell also is accused of pocketing more than $300,000 in unauthorized fees related to the failed sale of the Chino property, and selling the life insurance policies of two family members and pocketing the proceeds.

Some of the money was allegedly used to buy about a half-dozen properties in Arizona and California, including a multimillion-dollar condo in Long Beach for Novell and his girlfriend to live in.

In an emotional and heated meeting with the Stueves in early 2010, Meyer and Daily laid out their conclusions, telling the family that they had been receiving much less than they should have been, and that much of the cash had been pocketed by Novell. Many of them refused to believe Meyer and Daily for months afterward.

“Family members got mad at me for saying anything bad about Raymond Novell,” Meyer said.

Allen declined comment and referred the Business Journal to his attorney, who did not return a call for comment.

In a declaration to the court, Novell said he did nothing wrong and claimed he increased the value of the estate from $15 million to $31 million in eight years.

“These loans were made for investment purposes to generate income to meet the payment obligations to the CRUT notes,” he stated.

He claims to have made payments to family members totaling $17.5 million over the eight years, while they claim the payments totaled only $5 million. Novell’s attorney Burns said his client had fulfilled all his obligations.

“I don’t know why it is that they have millions of dollars of assets and received millions of dollars of benefits, and still contend that their friend and trustee stole money from them,” said Burns. “It doesn’t make sense to me. It’s easy to make allegations.”

A misunderstanding?

Katzenstein, the outside lawyer, said that cases involving alleged misdeeds of trustees can be tricky. Because trustees are charged with investing and handling complex matters, it’s possible that what may appear at first to be self-dealing may not be.

“There’s a possibility that these transactions were legit and the beneficiaries just don’t get it,” Katzenstein said. “I’ve had cases where we’ve alleged trustees have done all sorts of bad things, and when we get through it, at the end of the day it just looked like it because we didn’t understand exactly what we had in our hands.”

Indeed, Meyer admitted that he still doesn’t have a complete understanding of all of Novell’s actions, and said one reason the lawsuit was filed was to reach that understanding. However, the family is convinced of wrongdoing.

Meyer and Daily have uncovered what they believe to be damning evidence, including a memo from Allen to Novell they’ve dubbed a “bank robbery note” that allegedly outlines the steps to loan themselves money.

“When it was all laid out for us, it just made sense,” Arthur, 68, said.

Due in part to the legal limbo, payments from the trusts stopped a year ago. The family still owns properties, including the Chino parcel, but estimates on its worth vary widely.

Family members expressed doubt as to whether it will be possible to recover whatever money was allegedly lost. After some of them spent their entire lives working for the business, it’s clear they envisioned a different kind of retirement.

“It’s been a difficult year, coping with the lack of income and seeing how much of our money went out to people who should have had no business with it,” said the heavily indebted Claverie.