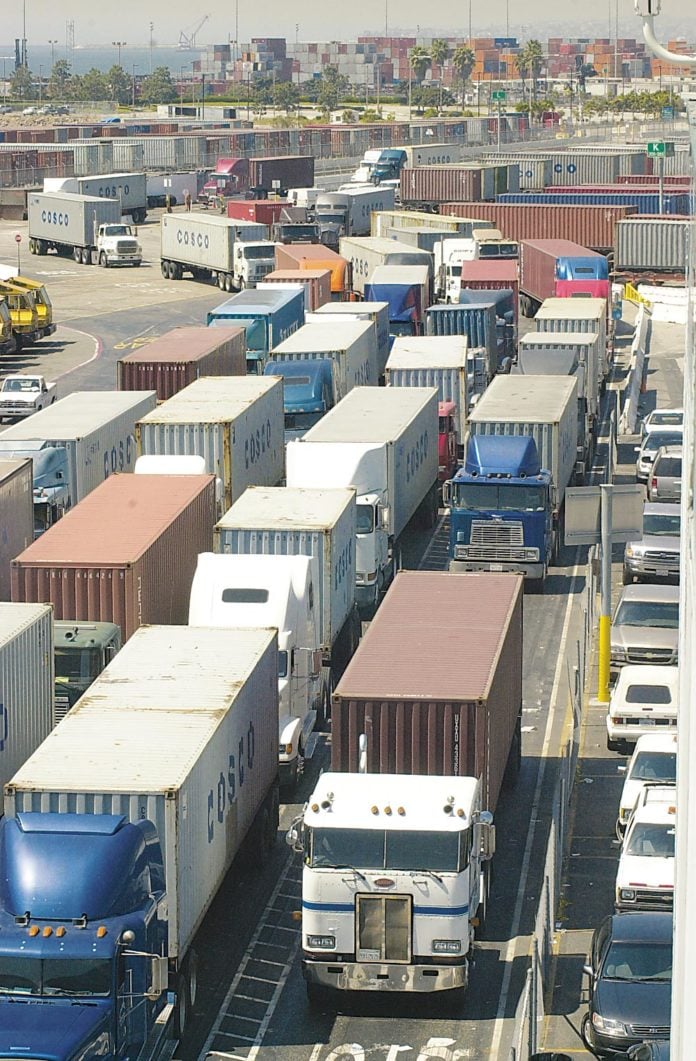

Nearly 12 months into a program that paid dozens of trucking companies $44 million to upgrade vehicles serving the Port of Los Angeles, the vast majority of subsidized trucks have not made the minimum number of trips to the port.

In fact, port officials said this month, more than 390 of them have not visited even once.

And the biggest recipient – Swift Transportation Corp. of Phoenix – and two other Arizona trucking companies now face a boycott started by the city of Los Angeles that theoretically could excuse them from their obligations entirely. That would mean more than 16 million public dollars would be lost.

Some critics of the port’s Clean Trucks Program are saying this is the latest evidence of a flawed program. Said Richard Haft, general counsel to a local company that didn’t get any incentive money: “The port handled this horribly.”

For its part, the port defends the program for achieving its clean-air goal. “The whole purpose of the program was to ensure that we had a good supply of clean trucks,” said John Holmes, the port’s director of operations, regarding the incentives paid under the Clean Trucks Program. “There was some uncertainty as to how it would work out.”

The plan began in 2008 when, under pressure from environmentalists to improve air quality, the port created the Clean Trucks Program requiring all trucking companies doing business there to aggressively reduce big rig emissions. The old fume-spewing diesel trucks were replaced with cleaner burning models, such as those fueled by clean diesel or liquefied natural gas.

Fearing there wouldn’t be enough low-emission trucks to go around, port officials went a step further. They committed $44 million in public funds as a financial incentive for truck companies to upgrade their vehicles, each of which can cost $150,000.

Specifically, each company participating in the program was given $20,000 for each low-emissions truck it bought. Each of those trucks was committed to make at least 300 pickups or deliveries annually at the Port of Los Angeles over the next five years. (The nearby Port of Long Beach also has a Clean Trucks Program, which is separately managed and has a different incentive program.) All told, officials say, about 100 companies were given subsidies for some 2,100 trucks.

With the end of the program’s first year looming, however, it appears that the companies’ promised goals are far from being met. To date, officials say, only about a third of those given money are expected to deliver on their promise of 300 port trips by the fiscal year’s June 30 end.

“What that means is that about 70 percent will not make the required number of trips the first year even though they’ve signed a contract,” Holmes said. “It’s the same as if you hired somebody to remodel your kitchen; they say they’ll be done in 30 days, and then hit some snags.”

In all, 393 of the 2,100 subsidized trucks have not made a single call at the port. Officials would not identify the companies that own those trucks.

Both the companies and the port characterize the main snag as the recession, which reduced port business 14 percent last year.

Add to that the carriers’ better-than-expected response to the port’s offer of financial incentives, and the result, some say, was predictable; an oversubscribed port with too many clean trucks and not enough loads.

Critics say the economic downturn was under way when the port started giving away public money. But port officials say their planning for the incentive program began early in 2008, before the full dimensions of the economic crisis were clear.

And they are quick to point out the apparent larger success of the Clean Trucks Program. Originally designed to achieve an 80 percent reduction in emissions by 2012, the program has nearly reached that goal now. A full two years before the deadline, about 90 percent of the trucks running in and out of the port are clean.

Sorting out

Cleaning up the incentive program, however, may prove to be more daunting.

According to the agreements signed by the participating companies, the port can demand that a portion of its subsidy be returned for any year in which a given truck fails to make the minimum number of required trips. Port officials say that still is an option. However, they seem more inclined to make the problem disappear by revising terms to lower the bar.

“There’ve been so many trucks purchased under the program that, combined with the downturn in the economy, there hasn’t been enough for them to do,” said Cindy Miscikowski, president of the Los Angeles Board of Harbor Commissioners, which oversees the port. “We want to keep them on board, so we’ve got to meet them half way.”

Among the changes being considered are reducing the annual number of trips required to qualify for the incentive, allowing participating companies to average the number of trips throughout their entire fleet and giving companies credit for trips to the Port of Long Beach as well as Los Angeles.

Port staffers say they will present their final recommendations regarding the matter to the board in mid-June, with immediate action expected.

Also awaiting action is a decision on whether to boycott Arizona over that state’s new immigration law. Earlier this month, the Los Angeles City Council voted to ban official travel and block future contracts with business concerns in the state. At the same time, the council asked the city’s port, airport and utilities to review all contracts with any companies based in Arizona.

The port has given $16.4 million to three Arizona trucking companies to help them buy clean trucks. The biggest by far is Swift, which accepted $11.8 million from the city-owned port to buy nearly 600 trucks. If the harbor commissioners decide to abide by the boycott and kill the contracts, the companies could theoretically walk away with no obligations to pay back the money.

Because of that, a port spokesman said, it may not be in the port’s best interest to void the contracts. “We’ve already paid out the incentives,” spokesman Arley Baker said. “If we sever ties, there really is no recourse.”

Aggravating the situation is that Swift, at least, won’t meet the mandated number of trips.

“Clearly we won’t make the goal,” company spokesman Dave Berry said regarding the port’s requirement of 300 trips per truck per year. “I think everybody did the right thing for the right reasons, but the fundamental situation is that there are too many drivers and not enough trips. When we sent a man to the moon we made a mid-course correction; we’re confident that that’s what the port will do now.”

Certainly the port’s Clean Trucks Program has its share of critics”

Small truck companies have long complained the program favors big truck companies because Los Angeles requires that truck drivers be employees, not independent owner-operators. (The Long Beach program does not have the employee mandate.”

‘Huge problems’

Clayton Boyce, a spokesman for the American Trucking Associations, which is challenging the employee requirement of L.A.’s Clean Trucks Program in court, would not comment specifically on the efforts to provide incentives. Regarding the Clean Trucks Program in general, however, he said: “There have obviously been huge problems with the way the Port of Los Angeles has gone about the entire plan.”

And Haft, general counsel for USC Intermodal Services Inc., a small Carson company that until recently was in both the trucking and warehouse businesses, said that mismanagement of the incentives program has badly hurt his company, which recently dismissed 50 workers and got rid of its 39 trucks.

“This is one of the most annoying things that has ever happened to us,” Haft said.

In 2008, USC Intermodal applied for the incentive program and – expecting to receive an initial $580,000 plus $290,000 for added trips later – signed contracts to buy $4 million worth of clean trucks, he said.

Because of a missed deadline, however, the incentive money never arrived. And that, combined with the recession, eventually caused the company to default on its loan.

USC Intermodal’s management takes full responsibility for the missed deadline, Haft said. But he characterizes the port’s incentive program as “administered horribly. The whole program was a giant giveaway without any proof that these trucks would actually be used in the port,” Haft said. “They didn’t look at the historical use of the port, just handed out a bunch of money without any proof.”

Should the problem be solved with a “mid-course” correction?

Heck no, according to Haft. “The port should sue to get its money back.”