Promises Treatment Centers became famous for its Hollywood clientele, including starlets Britney Spears and Lindsay Lohan. But when those stars suffered relapses, the sordid news was splashed over the tabloids and made Promises famous in an unwanted way.

Indeed, Promises got a reputation as a high-dollar Malibu getaway for wayward celebrities rather than as a serious drug and alcohol treatment center.

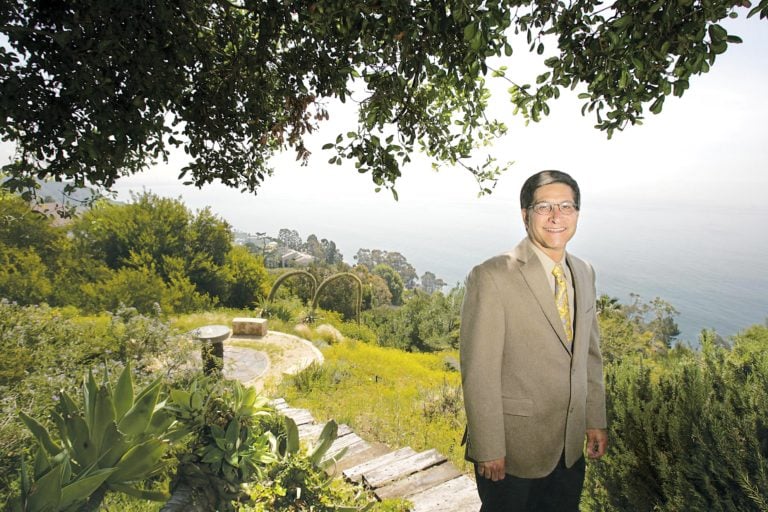

So when David Sack acquired the treatment program and its Malibu and West L.A. campuses in 2008, the psychiatrist had a big job: rehab the rehab centers.

Job 1 was to cut down those high-profile episodes of backsliding. “People do relapse,” Sack said. “And if I’m a celebrity and I relapse, it’s all over the tabloids. When treating celebrities, you are associated with their successes and failures.”

Sack said that Promises’ role as rehab center to the stars is the proverbial two-edged sword: It’s a source of pride and prejudice.

“It’s a challenge for us. We are doing everything we can to protect (celebrities’) anonymity and make sure they get the best care and treatment, and hope success will come back in a positive way to them and to us. But there are times when people will fail spectacularly, and we will get attached to that, too.”

Spears entered the Malibu rehab program in 2007 after shaving her head at a San Fernando Valley salon. She left Promises the day after she voluntarily checked into the program, but then quickly returned and completed treatment. However, there were public doubts about whether she had truly made a change; a court later placed Spears’ affairs under a permanent conservatorship in a sign that she hadn’t turned her life around.

Lohan also entered the Malibu program that year after getting busted for driving under the influence, but got another DUI several months after her treatment.

To head off those kinds of episodes, Sack has emphasized the program’s follow-up care system. He has the staff monitoring discharged patients instead of just letting them go.

In addition, he upgraded the Promises staff, recruiting licensed professionals with expertise in disorders such as depression and the latest celebrity problem – sex addiction. The program had focused on traditional 12-step recovery methods, but Sack now offers more involved mental health treatment to patients with drug and alcohol addictions.

Celebrity relapses weren’t the only problems for Promises.

The center was hit with several breach-of-contract and unfair-business-practices lawsuits in 2007 by former patients who claimed they were kicked out of the program and refused refunds. Promises denied the allegations. Sack said all of the lawsuits have been resolved. An attorney handling one of the cases said it was resolved, but would offer no other information.

What’s more, the California Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs has been investigating Promises to determine whether the center provided medical care without a license.

Promises isn’t allowed to offer medical care, but it can bring in doctors to treat patients as independent contractors. Sack said this is made clear to all patients.

“There is no centralized medical staff,” he said. “Our doctors provide services to clients, but they are not our employees and we don’t regulate the practice.”

It appears Promises is repairing its standing.

Heidi Kunzli, founder of Laguna Beach-based Prive-Swiss – an ultrahigh-end rehab treatment program that charges $100,000 for in-home treatment – said Sack’s reputation in the industry gives Promises credibility. Promises and another facility in Tucson, Ariz., are the only programs to which she refers patients.

“I know the practitioners and professionals at Promises and I know they are serious and they are good,” Kunzli said.

Changing ways

Richard Rogg founded Promises in 1989 in West Los Angeles, and he eventually opened a second facility in Malibu.

Promises charges $38,500 for a 90-day stay at its West L.A. facility, while treatment at its Malibu location – with panoramic views of the ocean and perfectly manicured lawns – starts at $54,500 for a 31-day stay. Sack declined to discuss Promises’ financials in detail, but said that the center posted its second-best year in 2009. (The Business Journal reported in 2006 that Promises brought in more than $15 million a year in revenue.)

Promises Malibu, which is located on two estate-size plots in the hills, offers such amenities as a tennis court, meditation areas, gourmet meals and 300-thread-count sheets. The lavish treatment and costly price tag have made Promises the target of jokes by comedians such as Jay Leno. But Sack said the picturesque setting was what first attracted him to Promises.

Sack, who has 28 years of experience in clinical, research and administrative psychiatry, first contacted Promises several years ago when he needed subjects for a clinical research study on a new treatment for alcohol addiction.

He was impressed with the relaxed, homelike environment Promises offered its patients, and thought the atmosphere made treating people with addictions more effective.

“Most settings that I’ve worked in, whether a hospital or community mental health clinic, create an obstacle to treatment,” he said. “They are bureaucratic settings and there is a tendency for everyone to get the same treatment, especially in chemical-dependency settings.”

About three years after Sack first visited Promises, he approached Rogg about acquiring the centers. Rogg told him he wanted to sell.

Sack purchased Promises through his company, Cerritos-based Elements Behavioral Health Inc., for about $30 million. Venture capital funds Frazier Healthcare Ventures and New Enterprise Associates, both of which invest in health care companies, helped cover the purchase. Rogg continues to work with Promises as a strategic consultant, and is a minority shareholder and partner.

After Sack took over Promises, he focused on the relapse problem, but that wasn’t his only change. In fact, early on he met with each employee to learn how he could improve business operations.

“I wanted to get an idea of what they liked, didn’t like and what they felt was working,” Sack said.

Sack quickly updated the phone and information technology systems at both locations. He then upgraded the West L.A. facility, which doesn’t get the same attention as Promises Malibu, by renovating the office space, group rooms and furnishings.

He also provided financial training to managers at both facilities so they would have an understanding of how the organization operates.

“Most staff had little experiencing with finances,” Sack said. “We invested a lot of energy into teaching them how to use financial reports and create an open financial management structure so they could be partners in this venture. That was a big change internally.”

Previously, he said, managers at the center didn’t really understand that they were running a business.

Sack then turned his attention to improving the centers’ treatment programs. He started a service program where patients volunteer with organizations such as homeless veteran projects while they are being treated. He upgraded the staff and contracted with more licensed professionals who provide care in a wider range of areas, including post-traumatic stress disorder, sex addiction and other compulsive disorders.

Susan Blacksher, executive director of the California Association of Addiction Recovery Resources, said Sack is making the program better by not just treating a patient’s drug and alcohol issues.

“More and more, people of good programs are dealing with the entire person,” Blacksher said, “including an assessment of any underlying medical or psychiatric needs that could interfere with a person’s ability to stay with a commitment of a more sober lifestyle.”

A big part of Sack’s efforts have been focused on improving Promises’ follow-up care, which he said will help patients remain sober and allow staff members to better track information such as relapse rates.

He formed additional Promises’ alumni groups, which serve as support systems for recovering addicts. There were groups in Malibu and Los Angeles – and also in New York, for people who had come for treatment. He set up groups in San Diego and San Francisco, and plans to organize groups in Boston and Chicago.

However, Sack realizes that Promises can’t reach all of its former patients through alumni groups alone. So in July, the organization started a system where staff members call former patients weekly during the first month after they leave the program. Thereafter, staff members call former patients once a month for the next six months.

Setting goals

What’s more, Promises started setting goals for discharged patients. They are now held responsible for attending 12-step meetings, finding a group home and sponsor, and remaining sober. Sack is looking for ways to monitor discharged patients in far-flung locales through social networking sites and applications.

Thus far, Sack said Promises has been collecting data from alumni group meetings and phone interviews to get a more accurate picture of the relapse rates of former patients. He said the most recent data shows that 79 percent of Promises’ alumni were continuously sober for 90 days. The national relapse rate for that period is 40 percent to 60 percent, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Now that Promises appears well along its own rehab program, Sack is thinking expansion.

He said he expects to acquire at least one additional treatment facility in California. It would not be a Promises facility, however, it would be part of his Elements Behavioral Health system. But he wants to extend the Promises brand by opening a facility in the Northeast United States.

Kunzli, of Prive-Swiss, said that’s a smart move because there’s a demand for high-end rehab programs on the East Coast. She’s setting up her own program in Connecticut.

“There’s a huge demand, people east of the Mississippi don’t want to fly out to California anymore because flying is such a hassle,” Kunzli said. “And there’s a population of people that could pay for it.”