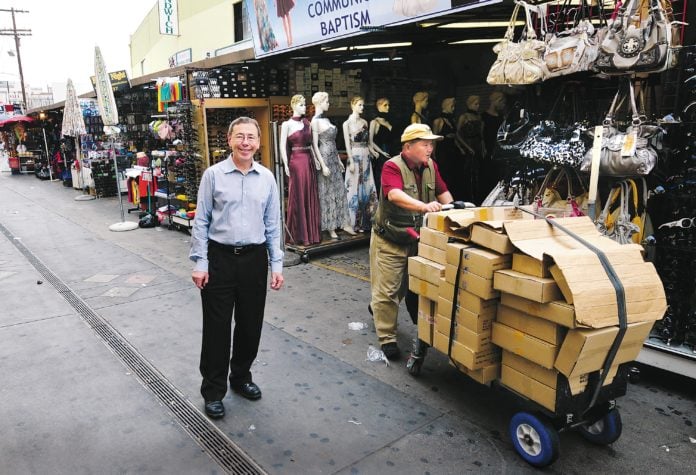

By day, L.A.’s Fashion District draws thousands of shoppers looking for bargains on stylish jeans and electronic gadgets. By night, the downtown neighborhood is a ghost town.

Plans are in the works to bring in crowds after dark, too. The Los Angeles Community Redevelopment Agency is leading an effort to line the streets of the 101-square-block district with housing, parks, restaurants, entertainment venues, hotels and retailers.

But tensions have already emerged over the proposal. Some business people in the district fear that the CRA’s plan to spruce up the area will lead to higher rents, and drive out much of the sewing, warehousing and wholesaling businesses that give the area its character and economic backbone.

The CRA has scheduled a July launch for a yearlong, $1 million study – dubbed the Fashion District Design for Development – offering options for transforming the district into a 24-hour community.

“It’s a major effort for us,” said Jenny Scanlin, CRA project manager who’s overseeing the study. “And one that I think is long overdue and one that will have a positive impact on the district over time.”

Scanlin said that the city government agency could put millions of dollars into redevelopment of the Fashion District.

Kent Smith, executive director of the Fashion District’s Business Improvement District, has been working with the agency to get the study started. He said the district, which generates more than $5 billion in annual economic activity for the city and employs 37,000, needs a master plan that will bring more private investment to the district.

“The Fashion District hasn’t always been at top of mind with the city and CRA,” Smith said. “And we’ve tried to tell them that we’ve got some real needs in the district that need to be looked at.”

The biggest issue for the long term is zoning. Developers want to know what they can build and where, and whether there will be conflicts if fancy new offices or condos are built next to industrial space.

However, Smith hopes the study will initially focus on the district’s basic needs. He hopes the study will recommend better access to public transportation, especially near the Metro Blue Line along Washington Boulevard where the Santa Monica (10) Freeway creates a kind of barrier. He also cited the need for infrastructure improvements such as lighting in the crammed, teeming Santee Alley and updating antiquated storm drains.

But he said the zoning changes are important, too. He noted that “chicken slaughterhouses” are allowed in some sections of the district. A chicken “processing plant” located near one of the district’s major wholesale marts is currently operating.

The zoning changes would also make it easier for the district to lure mixed-used projects.

“We are hoping that once the CRA plan gets started, we can get our industrial zoning changed so it can become more flexible and allow mixed-use, which is important for our success,” Smith said.

Resident obstacles

The district doesn’t have a great track record in residential development.

Some high-profile residential projects that have come on line in the district, such as Santee Village, a $130 million mixed-use development, have faced tough times. The Santee Village condo project went into foreclosure in 2008, and now Bank of America owns the largely empty property. A Rite Aid store also could not survive.

One problem is that the area doesn’t have a good amount of the amenities that support residential developments, such as parks and parking.

Mark Weinstein, whose MJW Investments developed Santee Village but later sold the project, said it’s difficult to convince people to move to the district. He favors the CRA’s goal, however.

“I think it’s a great idea, but it takes a lot of money to produce the proper parking and infrastructure,” Weinstein said. “And you have to get people from the office buildings and marts to stay at night.”

Smith said there are 2,000 residential units in the district. He points to the success of the Emil Brown Lofts, a 38-unit development near Santee Alley that’s set to open in the coming months and already has rented 36 of its 38 units, which go for $1,285 to $3,600 a month.

What’s more, the noise and traffic from wholesale and manufacturing businesses are likely to hinder residential development.

“Would you mind living above a little store that sells garments on a retail basis? Probably not,” said Iqbal Hassan, president of commercial real estate brokerage Quantum Associates, who has been representing landlords and tenants in the Fashion District since 1987. “But it might be inconvenient for residents who have to put up with the noise associated with running business operations, which could include manufacturing, warehousing and distribution.”

Smith acknowledges that there are valid points to such skepticism.

“There’s justifiable apprehension,” Smith said. “All of the success of our district hasn’t been due to the city’s intervention, and people say maybe if they intervene they will do more harm than good. But we believe there is a genuine interest in the city to look at the district as a job generator and place of economic activity, and they want to help.”

Detailed look

The Fashion District has been slowly modernizing as property owners have invested millions to renovate old buildings in an effort to better accommodate the area’s booming retail and wholesale operations. For example, the Los Angeles Fashion Center, commonly known as L.A. Face, a 300,000-square-foot commercial condominium project opened in 2009 to primarily service the growing number of Korean-American business owners looking to own a space where they can display wholesale goods for buyers from department stores and boutique retailers. The center features 200 showrooms from about 1,000 to 1,400 square feet that mostly sold for around $1 million.

But there’s more to be done. Even though there have been improvements to some buildings in the area, the upper floors of others are vacant as garment manufacturers have moved from the district to Vernon, City of Industry, El Monte and foreign countries, notably China.

And some Fashion District property owners believe that a renovation of more buildings in the area could lead to the development of additional office space and residential units, in turn pushing up rental rates for the upper floors and potentially forcing out what’s left of the district’s manufacturing base, which depends on low-cost space.

“For some buildings, it will make sense to upgrade to creative office space and residential, and then you get an upturn in rent,” said Steve Needleman, chief executive of Anjac Fashion Buildings, which owns about 1 million square feet in the district. “But I want to keep manufacturing.”

He said the sewing shops needs to stay downtown in order to keep jobs in Los Angeles. However, other property owners might opt for rent hikes, he acknowledged.

Smith said the CRA study will ensure that any plan would bring added value to property in the area.

To accomplish that, the study will examine how to improve the area’s streetscapes and alleyways to create a more pedestrian-friendly environment and duplicate the success of Santee Alley, a retail passage in the district that sees foot traffic volume on the weekends comparable with Santa Monica’s Third Street Promenade.

The study will also include an analysis of adding bike lanes, bringing streetcars to the district and making it easier to park.

As for zoning, the study will map areas within the district most suitable for housing developments and businesses that serve residents. It will recommend zoning changes to ensure that development in the area best serves the apparel industry.

“It’s about examining the assets and some of the issues within the district,” said Scanlin at the redevelopment agency. “And coming up with short- and long-term solutions and looking at an overarching investment plan for private investment as well as public investment to the area.”