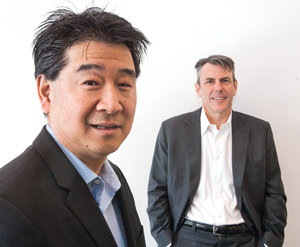

A $6 million loan to a family art business hardly registers as a major deal for Warren Woo, a veteran investment banker who estimates he’s done more than $25 billion in transactions over the course of a career spent at some of the world’s leading financial institutions.

But this modest transaction was maybe his most important: It was the first for his new firm, Breakaway Capital Partners, and it marked Woo’s re-entry into deal-making after a tumultuous 2014 in which he was sued and fired – and later apologized to – by his most recent employer.

When Woo joined Chicago private lender Monroe Capital in 2011 to lead the firm’s new L.A. office, it was seen in local finance circles as a coup for Monroe, given Woo’s long resume.

The match soured, though, and ended ugly in June, with Monroe not only suing Woo and claiming he stole trade secrets, but publicly firing him – a rare move in the clubby finance world. But Monroe recanted in December, and now Woo is back in action, doing deals at his new Century City firm.

Armed with $50 million from A-list investors – including big-name investment banker Ken Moelis and billionaire Panda Restaurant Group co-founders Andrew and Peggy Cherng – Breakaway just closed its first deal, providing a loan and taking an equity stake in the parent company of Morgan Hill’s Thomas Kinkade Co., which sells and licenses the late painter’s art.

While last year’s events were admittedly stressful, Woo said none of his investors bailed amid the turmoil.

“Fortunately, my reputation preceded me,” said Woo, 54.

Monroe Chief Executive Ted Koenig declined to comment on Woo and Breakaway for this article.

Family tree

Woo began his investment banking career in 1986 at the Beverly Hills office of New York investment bank Drexel Burnham Lambert, made famous by Michael Milken and his high-yield bond shop. That’s where Woo met Moelis.

When Drexel collapsed in 1990, Woo joined Moelis and other Drexel alumni at the local bureau of now-defunct investment bank Donaldson Lufkin & Jenrette. He would later follow Moelis to Swiss bank UBS, where he rose to lead the firm’s global leveraged finance and financial sponsors division before retiring in 2006.

Moelis coaxed Woo out of retirement the following year to join him as a founding partner of his new New York investment bank, Moelis & Co. But Woo quickly moved on.

“I realized I didn’t want to be an investment banker long term,” he said. “It’s the reason I retired from UBS.”

He had been thinking about raising his own debt fund and had even secured some investor commitments, mainly from close friends and fellow DLJ alumni. Monroe, meanwhile, had an established lending infrastructure and was looking to raise more capital, something the well-connected Woo could certainly help with.

“It seemed like a good partnership,” Woo said. “It turned out not to be.”

Woo said he and Koenig, a former litigator, were simply not compatible.

“From the beginning, we just had contrasting views about almost everything,” Woo said. “My philosophy regarding investments, people and business generally were just very different than Ted’s.”

Lending opportunity

Mike Connolly, Woo’s partner at Breakaway, worked with Woo at DLJ and UBS before joining West L.A. private equity giant Leonard Green & Partners. When he left that firm in 2013 with the intent to start his own fund, he met with Woo to talk strategy. They initially considered getting office space together, and then at the end of the year, Woo asked Connolly to join Breakaway. They started actively fundraising early last year.

The Kinkade deal, in which Breakaway provided a $6 million loan to finance Westwood private equity shop Next Point Capital’s recapitalization of the company, is an example of the type of deal the firm wants to do going forward.

Breakaway’s core business model is lending to California companies with less than $5 million in earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, or Ebitda. The firm also plans to take a small equity stake in every deal.

Woo and Connolly see lending to these smaller businesses as yet another opportunity that’s been opened up to alternative lenders by increasingly strict regulations on commercial banks.

Those regulations make it easier for banks to lend to big, stable companies than to firms with smaller balance sheets. But Woo said his and Connolly’s expertise in complex financing transactions gives them a better understanding of the credit risk of smaller companies.

“It requires a lot more work and a lot better understanding of the company and what the risks are,” Woo said. “There’s no question it’s harder to analyze the credit of a smaller company as opposed to a bigger company.”

Power play

While the Breakaway name seems almost too perfect given what Monroe accused him of – stealing trade secrets to help start his own shop – Woo said he had the name picked out for years. It’s a hockey term, which is appropriate for a passionate fan of the sport who’s also a part owner of the National Hockey League’s Nashville Predators.

Woo bought a stake in the Predators in 2007 alongside high-flying Silicon Valley venture capitalist William “Boots” Del Biaggio III, who would later plead guilty to cheating investors out of about $100 million and using falsified brokerage statements to secure loans from several banks and other team ownership groups – including Los Angeles Kings owner Anschutz Entertainment Group – to finance his stake in the Predators.

Woo maintains that he was blindsided by Del Biaggio’s shenanigans and said he was asked to stay on by rest of the team’s Nashville, Tenn.-based ownership group and the relations between them have always been positive.

He can’t say the same about his relationship with executives at Monroe.

In June, the firm fired him – and took the unusual step of issuing a press release saying so – and also sued him, alleging he had forwarded emails containing confidential deal information from his Monroe address to his Breakaway address, then deleted the original emails. Monroe argued Woo planned to use those emails to poach Monroe clients for his firm.

Woo said that’s simply nonsense.

“There was nothing in any of those emails that was even remotely proprietary or a trade secret,” he said.

Then why delete them?

“I have always used my Inbox and Send folders as my to-do list,” he said. “I routinely delete emails from both. I had no idea they would file a lawsuit since I wasn’t doing anything wrong.”

Peter Nolan, a managing director at Leonard Green – and an investor in both Breakaway and Monroe – said he never thought there was any merit to the charges.

“The allegations were a canard,” he said. “I thought this was simply a negotiating tactic.”

If that was the case, it didn’t work. Monroe in December dropped the suit and reached a settlement with Woo. What’s more, Monroe’s Koenig said in a Dec. 4 statement that, “Upon further investigation, it is clear that Warren’s actions were not improper.”

Woo is legally prohibited from discussing the terms of his settlement, but sources close to Breakaway say it is their understanding that he received more than was contractually owed under the terms of his original employment agreement.

While Koenig declined to comment on Woo or Breakaway, he said Monroe plans to maintain a strong presence on the West Coast and looks forward to doing deals on Woo’s turf.

“Monroe has originated and agented a total of 26 deals on the West Coast,” Koenig said in an email to the Business Journal. “Fifteen of them are in California, and 11 specifically in Southern California.”