Elvis Presley’s induction into the U.S. Army in 1958 spurred a search for rock n’ rollers who could provide a facsimile of the King – or at least have sufficient looks, voices and charisma to serve as teen idols for the surging rock audience.

Enter South Philadelphia crooners Fabian Forte, Frankie Avalon and Bobby Rydell, who started singing love songs someone else wrote to swooning, screaming fans on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand.

The Beatles and other British invasion bands came along a few years later, explained Hollywood-based music manager Oscar Arslanian, and “these guys got kind of shoved to the side.”

Their years in the wilderness stretched until the late 1970s, when Fabian, Avalon, Rydell and a few other Baby Boomer rockers were rediscovered, laying the groundwork for a second act that’s going on 40 years. They’re regularly selling out palladiums, amphitheaters and casinos throughout Southern California and the world, belting out their hits from 60 years ago.

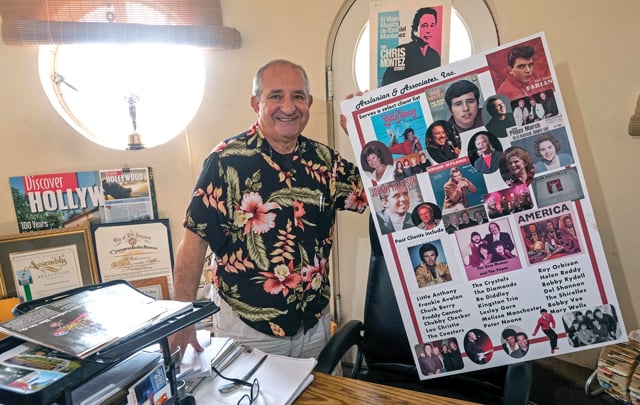

A number of the septuagenarian songsters make a living thanks in no small part to Arslanian, whose Arslanian & Associates developed a business model to cash in on the continued interest in rock-n-roll’s first pop stars.

It’s a niche business, left to entrepreneurs such as Arslanian and small to mid-sized venues such as the Greek Theatre, with capacity of 5,800, or smaller stages at Indian casinos.

It has, however, carved out a living for the artists, not to mention Arslanian and a coterie of collaborators and sometime competitors, such as Howie Silverman of Paradise Artists talent agency in Ojai and Nathan Goethals of Affordable Music Productions, a show promotion company in Upland.

“They have a particular audience,” Arslanian said of Fabian and the other artists that he currently manages.

Remember Brian Hyland, who won fame singing about the “Itsie Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini” back in 1960? Arslanian just booked him for a sold-out show for a summer festival in Italy.

“If they keep their health up, they will continue do well,” he said of his clients.

Casino connection

Arslanian spoke at his office in the quirky Crossroads of the World tower, also home to Discover Hollywood, a tourism-focused magazine he and his wife, Nyla Arslanian, publish quarterly.

Arslanian came to Los Angeles from his native Massachusetts in 1968 as a salesman for the Scott Paper Co. He moved to music and worked in various sales and public relations positions until he was laid off by Capitol Records in 1979.

“Then in late 1979,” Arslanian said. “I met an old teen idol, Fabian, and shortly thereafter he asked me to manage him.”

Arslanian had never managed talent before, and Fabian presented a particular challenge as he sought to backtrack from a public pronouncement he would never perform again.

Arslanian and Fabian both caught a break when Siegfried Fischbacher of Siegfried & Roy suffered a knee injury. That left a gap on the billing at a Las Vegas show where Chubby Checker and some other stars from the 1950s were lined up to open for the magicians.

Arslanian worked his Vegas contacts to land Fabian a role as emcee and performer in a fill-in routine with him and his cohorts from yesteryear.

“I came back to Los Angeles and said, ‘Wow, we got something,’” Arslanian said.

“These guys were in Howard Johnson’s lodges and stuff like that playing weekends. I saw the audience, and I saw the early baby boomer demographic.”

Arslanian took a chance on his budding theory, and produced a show at the Greek Theatre with Chuck Berry as headliner. It sold-out and the crowd ate up the throwback style. Arslanian started booking shows across the country, lining them up with venues for a 10 percent cut of their paydays.

For example, Arslanian might book a trio of artists, getting $20,000 per show from a venue. He’ll pay each artist $6,000, and keep $2,000 difference as his commission. The venue keeps the money from ticket sales and concessions.

Tickets at the Greek, or Saban Theatre in Beverly Hills could go for up to $75 a head. Arslanian said that he currently books each of those venues about once every other month. The majority of shows Arslanian books now are at casinos.

“They know the value of the music, and the audience that the music is bringing in,” Arslanian said of Southern California’s lineup of casinos, including Morongo Casino, Resort & Spa in Cabazon and Spotlight 29 in Coachella.

The casino trade has blossomed along with the second acts of Arslanian’s clients thanks to a 1988 federal law that let American Indian tribes open casinos. The number of states with gambling resorts has grown from two to 39 over the past 30 years, with casinos adopting the Las Vegas model of entertainment to keep customers near slot machines and poker tables.

Living for live shows

Another market factor in favor of oldies tours is that live entertainment is a growing share of the music industry.

Forty-three percent of industry profits came from live music in 2016, according to a PricewaterhouseCoopers study, compared to 33 percent in 2000.

It’s a bigger factor for the early rockers is that live music is virtually their only source of income.

Few of them wrote their own songs, which means they aren’t in line for

royalties on the music itself. And royalties for recordings of their performances of songs prior to 1972 are subject to various state statutes, a quirk in copyright law that Congress is currently considering whether to eliminate.

“These older acts make virtually no money off their recordings,” said music lawyer, Kenneth Abdo of Fox Rothschild, adding that besides few sound recording royalties, “Nobody buys their albums anymore. The fan base already owns the greatest hits of 1958.”

There is also low overhead for these artists, noted Goethals, of Affordable Music Productions.

The shows consist of multiple artists sharing one backing band, Goethals said, and there are no “pyrotechnics” or other instances of expensive production.

Still, Goethals said, booking late ‘50s rockers, “is a niche business. If it were easy, there would be plenty more of me.”

Arslanian noted “actuarial tables,” will eventually stop the return on his late ‘50s rock investment. But he said that clients like Fabian have a few good years left. “These guys look great,” Arslanian said.