Zefr Inc. pulled off the nearly impossible two years ago by getting all the major Hollywood studios to stop being the bad guys who take down movie clips that fans post to YouTube.

Now, the Venice company is trying to do something that’s even harder for tech companies: make more money.

To that end, it recently acquired Pipewave Inc., a Boston ad tech firm Zefr hopes will boost the effectiveness of its ads. Executives at Zefr said the move to beef up its ad technology is the next step for a company that’s racking up more than 1 billion monthly views – for content it doesn’t own.

Zefr gets access to popular clips through a simple pitch to the studios: instead of forcing YouTube users to remove clips of movies they’ve posted, keep them online and let Zefr put advertising on them. Zefr’s technology scans the flood of new YouTube videos and discovers ones with copyrighted content. Then it attaches ads to them. Because the studios own the videos, they take the lion’s share of the resulting ad revenue.

Like nearly all of the companies making money on YouTube, Zefr gives the video site’s parent company, Google Inc., a cut of the ad sales. Zefr also takes a percentage, an amount executives didn’t disclose. Company executives said Pipewave gives it better control of how the ads are presented.

“Google builds great tech but they can’t build every feature that our partners are going to need,” said Zefr co-founder Rich Raddon. “Pipewave brought a whole host of knowledge and info into the company to help our advertising be more precise.”

Of particular interest was Pipewave’s ability to track how well a video advertisement is doing with different demographics. For example, if a studio had prepared several different promos for a movie, each designed to appeal to a different age group, Pipewave can make sure the ads that are tracking the best with certain ages are routed to the right viewers.

As Zefr begins to ramp up the number of videos it licenses, with a planned expansion into TV shows and sports highlights, the company is positioning itself as a middleman for advertisers and content creators. It’s a relationship Zach James, Zefr’s co-founder and chief executive, likens to a popular and brand-friendly TV presenter.

“We’re the Ryan Seacrest of tech. We just try to make the hits even more of a hit,” James said. “A studio or advertiser gets more out of the experience with someone like us.”

Pirates or fans?

By working out deals with all the major studios, Zefr pulled off a feat accomplished by few technology companies – including Apple Inc. and Netflix Inc.

Becoming a weighty presence on YouTube is actually the second stage for the three-year-old business, which began its life as Movieclips.

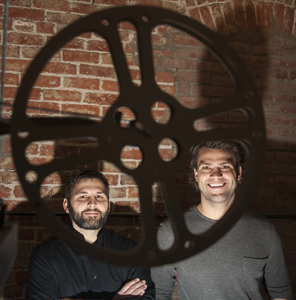

The company’s scope as a technology firm for movie studios can be traced to the co-founders’ history. James previously worked at the San Francisco office of Credit Suisse Group and helped oversee Google’s acquisition of YouTube. Raddon is from the film industry and was the former director of the Los Angeles Film Festival.

The two started Movieclips in 2009 with the goal of empowering fans who were posting snippets of movie scenes on the Internet. At the time, YouTube would voluntarily take down videos that violated copyright, but only upon a studio’s request. It made for an antagonistic relationship between the studios, which owned the movies, and the fans who were mostly trying to celebrate them.

“On YouTube, uploading a video is like hitting the ‘like’ bar in Facebook,” said James. “It’s not piracy; it’s passion.”

Studio executives did not respond to requests for comment.

Convincing the movie studios on the value of having scenes posted on YouTube required more than a change in perception; it prompted an argument about a new opportunity for advertising.

The technology that James and Raddon’s company developed has the ability to both identify copyrighted property as well as automatically discover key attributes about the video to help make the advertising more precise – so a trailer for a new children’s movie doesn’t play before a movie clip from “Saw III.” It’s a similar process to how music service Pandora maps out a song’s “genome” (its genre, tempo, subject matter) to pick a piece of music to fit a listener’s taste.

New plays

Last year, Movieclips changed its name to Zefr to reflect the company’s upcoming move away from just movies and into new areas of copyrighted material. Zefr has grown quickly in the past few years and has raised $28 million in venture capital; most of the company’s 150 employees work in a spacious warehouse on Venice’s artsy Abbot Kinney Boulevard.

Drew Baldwin, who runs TubeFilter, a site covering the online video industry, said Zefr has staked out a smart claim as a service provider rather than a creator.

“In the gold rush, the people who did best were the ones who sold the axes and the panning equipment,” Baldwin said. “Zefr is the same. They’re providing the tools increasing everyone’s chances of making money, but not investing too much themselves.”

But being only a service provider on YouTube has its drawbacks. While Zefr doesn’t have to take on the expense of producing content, it also takes a smaller cut of the revenue. Zefr executives did not disclose its share of the revenue split with the studios and YouTube. Most channels only have to share revenue with YouTube.

Zefr has no plans to produce content, even with the lure of getting a larger slice of ad revenue by posting original videos to its audience of more than 300,000 YouTube subscribers. It makes for a somewhat conservative stance by Zefr as the original channel industry continues to gain popularity, but executives there insist it’s a much smarter play.

“You’re absorbing a hefty upfront to make those videos,” Raddon said. “I understand why other people want own 100 percent of their material, but that isn’t our business model.”