The paperwork looked legitimate, even down to the footnotes. References checked out. The investment strategy seemed reasonable.

Alistair Waddell felt good about handing over $300,000 of his money to Diversified Lending Group Inc., a Sherman Oaks company promising healthy returns on investments in distressed properties. So good, in fact, that the retirement planner even recommended his clients do likewise.

“Everything checked out. All the things you look for, they all looked wonderful,” he said. “Too wonderful, in retrospect.”

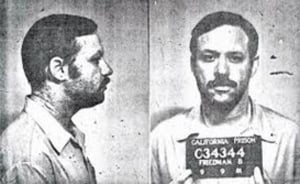

It turns out Diversified was one of the largest Ponzi schemes in California history, according to the authorities who shut it down in 2009. The alleged scam, run for years by a charismatic businessman named Bruce Friedman, cleaned out more than 1,200 investors, and bankrupted businesses and community organizations, including the Children’s Museum of Los Angeles.

The operations took in nearly a quarter of a billion dollars from elderly investors across the country. But as the aftermath unfolds, it now appears that those investors are likely to get back a tiny fraction of the money they put in.

Over the past month, a court-appointed receiver, who has been selling off Diversified’s assets, made the first distribution of funds to investors – a meager three cents on the dollar. And they might not get much more.

Most of the money Diversified took in was allegedly squandered by Friedman on bad investments or used to fund his lavish lifestyle. The 62-year-old drove a Bentley, flew on private jets, vacationed across the globe and donated millions to charity. City officials lauded him for his generosity. The Dodgers invited him to throw out the first pitch before a game.

But Friedman died earlier this year in a French prison, before standing trial on a litany of fraud charges that could have put him away for 390 years. Still, the FBI and Securities and Exchange Commission continue to investigate his empire, which included two companies employing nearly 20 people, and a charity headed by Friedman’s son.

The Business Journal reached out to dozens of people who knew Friedman – family, friends, associates, investors, authorities and more – and examined thousands of pages of internal documents and court filings to uncover details of the impact and aftermath of his alleged scheme, and to provide a better view of the person behind the debacle.

Two distinctly different pictures have emerged. Friedman was described as a big-hearted philanthropist, enthusiastic baseball fan and upstanding family man who would host Sunday brunches at his home; he was also, few people knew, a convicted felon accused of using lies and manipulation to steal the fortunes of retirees.

“Who we thought he was wasn’t who he was,” said Dina Kaplan, Friedman’s former sister-in-law.

‘Bright, articulate, honest’

Born in Baltimore and raised in the San Fernando Valley, Friedman had a “pretty typical” childhood, said his brother, Gary Friedman. When they could, the brothers would catch games at Dodger Stadium.

A bright kid, Bruce Friedman went to UCLA, graduating in 1970 with a degree in political science, according to the university registrar’s office.

After college, he stayed in the area, but struggled to find professional success. In the 1980s, he began looking to family and friends for investment capital, which he intended to lend out.

That effort went through several iterations, some more successful than others.

In 2000, Friedman was charged in New York with wire fraud after allegedly failing to secure a promised loan for a film company; charges were later dropped. In 2004, Lenders Depot Inc., the predecessor to Diversified, paid $500,000 to settle a lawsuit filed by an oil company also over a loan dispute.

It was in 2004, though, that Friedman hit upon a winning formula. As the economy was taking off and investment capital was becoming easy to get, he launched Diversified. The company offered what Friedman called premier financing, an “annuitylike” investment that would simultaneously fund a life insurance policy for the investor and provide returns of as much as 12 percent a year. Friedman told prospective investors their money would be used to buy “scratch and dent” properties, which would be fixed up and sold at a substantial profit, and that the investments would be completely insured by a major national company.

Stout and craggy skinned, with a wavy crop of ashen hair, Friedman was unimpressive in appearance, but those who knew him said he was personable and a smooth talker, and he had a knack for gaining people’s trust.

He also had an authoritative air. He hosted seminars in the San Fernando Valley for insurance and investment professionals to pitch his company. He would often speak of “doors,” or income-producing properties in his portfolio, and claimed the assets were worth billions.

Waddell, who attended one of those seminars, was struck by how knowledgeable Friedman appeared to be about even obscure tax laws.

“He came across as very bright, very articulate, honest,” said Waddell, a public accountant by trade who had gotten into retirement planning through a friend in the insurance business. “He understood how to use different types of trust vehicles and he seemed to have his act together from a knowledge of the real estate business.”

Friedman established relationships with numerous insurance brokers and incentivized them to push their clients to Diversified by paying commissions, a common practice in the industry. Some of the more active brokers pulled in as much as $1.7 million in commission pay, according to court filings.

Friedman also crafted elaborate and professional-looking financial statements. David Gill, a Century City attorney who is serving as the receiver in this case, noted that Friedman established a “veneer of respectability” by dropping references to well-known firms.

At various times, Diversified’s filings claimed associations with Jackson National Life Insurance Co. and law firm Kirkland & Ellis, and said it was planning to engage Deloitte to audit its financial statements. In fact, those firms either had limited interactions with Diversified or none at all.

“He had a lot of those pieces in place to convince people that this was a good, solid program,” Gill said.

To accommodate a staff of about 20, Friedman leased office space on the 12th floor of the prominent Valley Executive Tower, a bustling 21-story high-rise in Sherman Oaks that also housed respected financial organizations such as banking giant JPMorgan Chase & Co. and venture capital firm DFJ Frontier. The City National Bank name is at the top of the building. Diversified looked like it fit right in, with well-appointed offices replete with original artwork.

“It was a well-done, professional office,” Waddell said, “like you would expect at any investment company or law office or public accounting firm.”

Big spender

Investments started pouring in. A retiree from Morro Bay put in $876,000. A couple from Wellington, Fla., invested $224,000. A pharmaceuticals executive in Atlanta handed over $625,000. A social worker in Altadena committed $200,000.

Most investors were steered to Diversified from financial planners or insurance brokers who had been swayed by Friedman or knew someone who had.

Jama Bowlby, a 69-year-old retiree in Michigan, and her husband, Orrin, were approached by representatives from American Benefits Concepts Inc. Not only did the Bowlbys hand over their savings – about $100,000 – but they even refinanced their home of 32 years for extra cash.

“We weighed it over and checked things out and we didn’t find anything bad through the Better Business Bureau,” she said. “So we decided that we’d go with it.”

Many of those who gave money to Friedman said they were comfortable because it looked in every way like a legitimate business and, most importantly, because investors always received their expected payouts on time. Friedman was accessible, too. He would refund money in the rare cases when clients had concerns, said one former employee.

By 2006, Diversified’s assets were ballooning. Friedman – the company’s chief executive, president and sole shareholder – made all major decisions and had full control over the finances, and he began spending lavishly.

On Oct. 2 of that year, he dropped $128,000 in a single trip to JR’s Diamond & Jewelry in Sherman Oaks, according to a later indictment from the U.S. Attorney’s Office. Two months later, he bought a new Bentley for $245,000. Then he spent $114,000 and $111,000 in separate trips to JR’s in early 2007. Shortly thereafter, Friedman picked up a $99,000 Lexus LS600 and dropped an additional $89,000 on a Mercedes-Benz CLS550.

According to court filings, Friedman diverted $57 million for his own personal use, but it wasn’t all for cars and jewelry.

He paid his ex-wife’s credit card bills; spent $2 million on travel, hotels and gambling; purchased an $8.5 million home in Malibu and interests in five private jets; bought gifts, including homes, for family and friends; and paid $340,000 for three years of Dodgers season tickets.

As John McCoy, associate regional director of the SEC’s L.A. office, put it, Friedman was living “a larger-than-life lifestyle.”

Still, his spending didn’t seem to raise any red flags.

“He was somewhat humble, which is hard to say when you drive a Bentley,” said one former Diversified employee who asked not to be named. “He seemed like he was just a good person, but it turns out he was a complete crook and a sociopath.”

Friedman also used investors’ money to establish a charitable organization benefiting children. He gave $1 million for the construction of a park in Calabasas for special needs kids; Brandon’s Village, as it is called, was named for Friedman’s nephew, who is physically and developmentally disabled.

He also partnered with the Dodgers, giving about $50,000 to a team charity. Prior to the 2008 season, Friedman was invited to throw out the ceremonial first pitch at an exhibition game at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum that set a record for the largest crowd ever to attend a baseball game.

Later that year, Friedman pledged up to $5 million to the Dodgers Dream Foundation to build 42 baseball fields across Los Angeles. The Dodgers put out a statement calling the Friedman Charitable Foundation “one of its most generous supporters” and held a press conference at which Friedman appeared with Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa and then-team co-owners Frank and Jamie McCourt.

But Friedman’s biggest contribution was to the children’s museum. His foundation gave more than $3 million and pledged up to $10 million total.

“It had taken years to find a donor that was willing to pledge that kind of money,” said Cecilia Aguilera Glassman, who was chief executive of the museum at the time.

The money came after a chance meeting with Friedman, whom she said “seemed very passionate” about ensuring that the long-stalled effort to build a museum in Lakeview Terrace could be completed.

Friedman did use a portion of client funds for actual investments but none went to the scratch-and-dent properties Diversified claimed to be buying. Instead, Friedman pumped tens of millions of dollars into mostly questionable and sometimes bizarre deals.

He invested in a New Jersey toy company, a North Carolina RV campground and a documentary about a rock ’n’ roll photographer named Robert Knight. Friedman put a half-million dollars into an online doctor referral venture that never even got started and invested more than $4 million in a Texas wind farm that is now virtually worthless.

In 2007, Friedman approached the Motion Picture Hall of Fame, a group dedicated to promoting the movie industry, about developing a multimillion-dollar Hollywood-themed attraction in Las Vegas.

“For a man who had a reputation for being very smart, he made a number of investments – most of the investments we saw – that were almost irrational,” said Gill, the receiver.

Rapid fall

Ironically, Friedman’s alleged scheme collapsed as a result of what was arguably one of his most pragmatic investments.

By late 2008, Friedman had taken a large stake in Fonar Corp., a 30-year-old publicly traded maker of MRI machines in Melville, N.Y. Intent on buying the company, Friedman approached the largest shareholder, founder Raymond Damadian, and offered $5 a share, a massive premium over its stock price at the time.

The company did not respond, prompting a frustrated Friedman to take his offer public in a letter to the board. Shares surged on the offer, but the company said it was not interested in selling.

Though the acquisition attempt went no further, it set into motion a series of events that would kill Diversified in just a few months.

An article from Dow Jones Newswires about the Fonar tussle revealed details of Friedman’s background, including a previously undisclosed felony conviction for grand theft in the early 1980s: Friedman served nearly two years in California state prison for stealing $300,000 from his then-employer, Avery International Corp., predecessor to Pasadena’s Avery Dennison Corp.

On Dec. 16, the day that article came out, Friedman sent a letter to Diversified’s investors admitting for the first time that he had been in prison and had an unrelated bankruptcy filing a decade later.

“Although I am aware of no legal requirement to make these disclosures, my respect and appreciation for each of you, and my steadfast determination to protect DLG’s interests, compels me to disclose these regrettable events,” he wrote, citing media pressure for his decision to send the letter.

One Westlake Village investor, who asked that his name not be used, said he never would have invested with Friedman if his past had been disclosed. The investor had well over $1 million tied up in Diversified. He attempted to withdraw it all once he received the letter.

“I tried to get my money out but I couldn’t,” he said. “It certainly will delay my retirement.”

By early 2009, Diversified was being deluged with redemption requests that it could not fulfill. At the same time, regulators in California, Michigan and Arkansas stepped up scrutiny amid investor concerns about whether Diversified’s products qualified as registered securities.

The SEC, too, investigated and obtained a court order freezing the assets of Diversified and a related but defunct company called Applied Equities Inc. On March 5, 2009, Gill took a team of lawyers and accountants to Sherman Oaks and seized Diversified’s offices.

According to an employee who was there that day, the process was quick but confusing. Friedman called the staff into a conference room and told them the office was being shut down and they should go home. The whole speech took about 30 seconds and Friedman didn’t give details or answer questions.

The employees were floored. Several gathered in the building lobby to ask each other if anyone knew what was going on.

They were allowed to take some personal effects, but one employee tried to sneak out with jewelry that had been kept in the safe, Gill noted. Friedman, he said, was cooperative and seemed to believe that it was all a misunderstanding.

“I expected the worst and he was courteous, welcoming,” Gill said. “He answered the questions, wanted to explain everything.”

That same day, Gill and his associates changed the locks at the office, and they began copying financial records and analyzing electronic data. During the next few days, employees were brought in for individual interviews.

Once forensic accountants could examine the books, investigators came up with a final tally: Diversified had taken in more than $230 million, of which $190 million was either lost on bad investments or spent by Friedman. The rest was used in classic Ponzi scheme fashion to pay dividends to earlier investors.

McCoy at the SEC’s L.A. office called it “one of the bigger offering frauds this office has brought – certainly since I’ve been here and, I suspect, overall.”

Local organizations began scrambling to contain the damage. The Dodgers immediately canceled plans to build the baseball fields with Friedman’s charity and tried to distance themselves.

“Once the SEC came out with the Ponzi (allegations) we severed that relationship,” said team spokesman Steve Brener.

‘A very difficult position’

The children’s museum called an emergency board meeting. The decision was made to file for bankruptcy, which would protect the funds it had already received. But once the allegations against Friedman became public, Aguilera Glassman, the head of the museum, said new donations completely evaporated.

“Anyone that had an outstanding pledge that was due wasn’t paying it at that point because they wanted to see where this was going,” said Aguilera Glassman, who is now executive director of the Los Angeles Police Foundation. “Unfortunately, this just put us in a very difficult position.”

The museum’s fate is in limbo as city officials attempt to finalize financing plans. (See related article, below.)

Like the museum, Phoenix water company Sun West Bottlers LLC, which had received a $4 million investment from Friedman, and Montclair, N.J., toy distributor Makin’ Fun Inc., which got $5.5 million, both filed for bankruptcy protection as well.

The fallout also decimated the Sherman Oaks insurance community, as brokers lost money, clients and, in some cases, their jobs.

“There were some really high-end insurance agents in town who had been working with him,” Waddell said. “It took some of those guys to bankruptcy.”

Waddell, who has left the insurance business and returned to accounting, said he has had a lot of sleepless nights because of his decision to steer clients to Diversified. To set things right, he is in the process of repaying those investors out of his own pocket – about $185,000 in all.

“That’s business ethics,” he said. “As best I could, I helped make them whole with my own funds. I went from having a very nice, fat savings account to nothing.”

Meanwhile, other investors have filed suits against companies whose brokers recommended Diversified. At least a half-dozen local brokers with New York insurance giant MetLife Inc. allegedly steered clients to Diversified, and the individuals have been named in numerous suits. Jackson National of Lansing, Mich., has also been targeted by angry investors; at least two of its brokers were simultaneously employed by Friedman and convinced clients to invest, according to filings.

For some, the fallout has been more than financial.

Kaplan, Friedman’s former sister-in-law, said she has been accused of crimes she did not commit and has been a frequent target of personal attacks from those angry about Friedman.

“They’ve been lashing out at everybody in my family, everybody that’s remotely related to him,” said Kaplan, a lawyer in Calabasas, who said she had no involvement with Friedman’s business. “I’ve had people contact me online, telling me I was scum and that I ruined people’s lives, and that my child – who is disabled – was given to me because I was a horrible person.”

Friedman’s brother said he lost a significant amount of money that he had invested in Diversified but that he was excluded from efforts to recover funds because he shares the same last name as the man allegedly responsible. Gary Friedman, who had run an investment firm in Tarzana, said he is trying to move on and start a new life with his wife in Nevada after the “nightmare” of the last few years.

“It’s been horrendous,” he said.

Despite all the allegations against him, Bruce Friedman maintained until the end that he had done nothing wrong, that everything was a misunderstanding.

He claimed in court filings that investments he had made still had “the potential to generate substantial returns.” He pointed to Consolidated Healthcare Systems, a medical equipment company in which Diversified had taken a $26 million stake.

Friedman even convinced several previous investors – who had already lost considerable sums – to approach the receiver and attempt to buy back certain assets that Friedman believed were valuable.

In late 2010, Friedman told his brother that he had deals lined up outside the country that would allow him to buy back Diversified and pay back all of the investors.

While he was in Belize, authorities notified Friedman’s attorney that charges were likely to be filed. According to an FBI affidavit, Friedman promised to return to the United States, but instead went to France.

While he was in Cannes, a federal grand jury returned a 23-count indictment accusing him of fraud and money laundering. French police, at the request of the FBI, arrested Friedman outside his hotel.

While authorities arranged his extradition, Friedman sat for more than a year in prison at Aix-Luynes, a compound of rundown pink and white buildings in the south of France. He wrote letters to family members complaining about the lack of adequate medical care and limited access to legal aid.

On March 4, Friedman awoke with sharp chest pains. He complained to the guards, who summoned medical help, but Friedman died of cardiac arrest before doctors could arrive.

Friedman’s mother had a pacemaker, but Friedman himself had never had any significant heart problems, so his death came as a shock to his family. His body was cremated and the ashes were sent back to the United States; his family held a funeral several weeks later.

Some who invested with or knew Friedman have openly discussed their belief that he faked his death. One former co-worker declined to speak to the Business Journal over such concerns.

But Gary Friedman scoffed at the notion.

“He’s definitely buried,” he said.

Payback

His death, however, does not mean the end of the cases against him. The SEC recently filed a motion to substitute his estate for the person of Bruce Friedman, which will allow the agency to continue to pursue claims. Laura Eimiller, a spokeswoman for the FBI, also confirmed that “we do have a continuing investigation.”

The receiver, too, is still seeking assets that can be sold for the benefit of investors.

Gill has been able to sell off a number of Diversified holdings, including a house in Malibu, a 5-carat diamond ring and stakes in companies. He has also filed claims against dozens of family members, friends, co-workers and others who profited through Friedman. Many of those have been settled; those who profited are now repaying the ill-gotten gains.

Some claims, however, involve companies without sufficient funds to pay. Voyager Entertainment International Inc., a Las Vegas company in which Friedman invested more than $1 million, said it does not have the cash available to repay the receiver, according to court filings.

“There’s a lot that is not worth anything or is worth substantially less than he spent on it,” Gill said.

The recovery process has been slow, he said, because Diversified maintained few records and those that it did keep were largely fabricated. The financial records for 2007, for instance, claimed assets of $655 million; Diversified never had even half that much.

According to court filings, Diversified did not prepare balance sheets, statements of income or cash flow, and instead had only “incomplete electronic checkbooks maintained on QuickBooks.”

Perversely, Friedman’s death might turn out to be one of the most financially beneficial developments for investors. Friedman had taken out a $10 million life insurance policy on himself, which was recently paid to the receiver.

Including that money, Gill has recovered about $31 million thus far, and he recently made the first distribution to investors – about $5 million, or 3 cents on the dollar. The amount was small because some funds have been reserved for disputed claims and other dollars were used to pay secured creditors; also, the receiver has yet to obtain approval to distribute the life insurance proceeds.

Gill said he hopes to make at least one additional distribution, but declined to say how much investors could expect.

However, several people familiar with the asset recovery and fund distribution process said it is unlikely investors will receive more than 10 cents on the dollar by the time the case is closed.

Many investors have come to accept that they won’t get much of their money back, but some still hold out hope.

Bowlby, the Michigan retiree who refinanced her home and put most of her family’s savings into Diversified, said she regularly fills out paperwork in the hope that she can get something, anything.

Since Diversified was shut down and the assets frozen, the Bowlbys have lost their home to foreclosure and filed for bankruptcy protection. They have moved into a mobile home and are getting by on Social Security.

“We lost everything,” said Bowlby, her voice quivering. “I don’t know whether we’re ever going to get anything back or not. I just wished that things would have worked out differently.”