Los Angeles is known the world over as the home to movie stars and beautiful people, with faces and figures perfected by cosmetic procedures.

Sure, there are probably more plastic surgeons per square mile here than just about any other city, but the area also is home to many companies with beauty products based on cutting-edge science.

“This is what the beauty industry is evolving into. Not everyone wants to go under the knife, but people want to spend their money on products that work,” said Elise Minton, executive beauty editor of New Beauty, a magazine that covers science-based products and procedures.

Some of the beauty products even need regulatory approval.

“Rigorous science is the next wave in the beauty industry,” Minton said.

Los Angeles does not yet have a scientific beauty company the size of Allergan Inc., the Irvine company with revenue in the billions that makes Botox, an injectable drug that removes wrinkles. But what it does have is a good dose of small to midsize companies with startlingly diverse specialties.

There’s Lifetech Resources Inc., a Chatsworth company that is using amino acids called peptides to stimulate the growth of eyelashes. (See sidebar page 26.)

Obagi Medical Products Inc. is a Long Beach company that makes prescription products to prepare and heal skin for cosmetic surgery.

There’s even a biotech startup, Kythera Biopharmaceuticals Inc. of Calabasas, whose lead drug candidate – an injectable fat dissolver that can eliminate sagging jowls – requires Food and Drug Administration approval. (See sidebar page 27.)

All of them are trying to tap into a global market for premium beauty products that hit $79 billion at the end of last year, according to London market researcher Euro Monitor International. Of that, anti-aging products are the growth leaders in the United States.

“Baby boomers continue getting older, and people did not stop being vain, even during the recession, so big opportunities are there,” said Annabel Samimy, an industry analyst with Stifel Nicolaus & Co.

Building niche

There’s good reason why Los Angeles is home to so many science-based cosmetic companies. Most of them were founded by entrepreneurial doctors who built on their success in treating the aesthetic shortcomings of Hollywood’s elite.

For example, Physicians Formula Holdings Inc. was started by an allergist in the late 1930s who pioneered the hypoallergenic beauty segment. The public Azusa company is still going strong and its latest makeup formulas are seizing on another trend: using natural mineral extracts and plant-based sources such as bamboo silk.

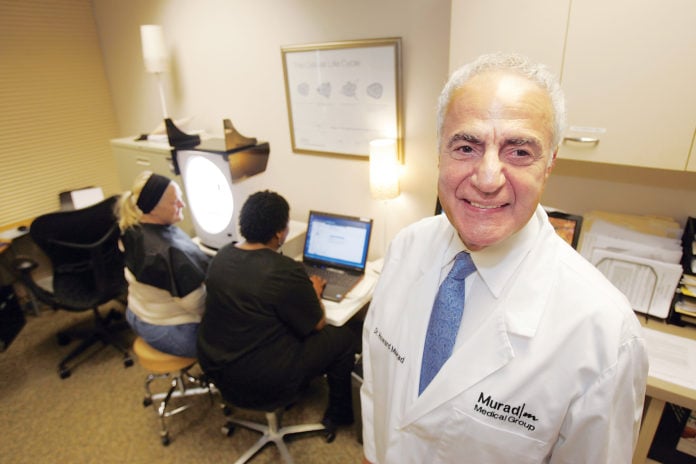

Twenty years ago, Dr. Howard Murad, a local dermatologist, popularized the use of alpha hydroxyl acids as an alternative to Retin-A to treat troubled skin. His El Segundo company, Murad Inc., is best known for its consumer skin care products sold in specialty beauty stores and on the Internet. He also was one of the first to sell his products through doctors’ offices. That’s a far more limited channel than mass-market retailers, but the cachet it showered on his products allowed him to charge premium prices. (See sidebar page 26.)

Murad success has been followed by Obagi Medical Products, founded in 1988 by Dr. Zein Obagi, a Beverly Hills celebrity dermatologist. The products are only sold at doctors’ offices, with some requiring prescriptions.

Unlike Murad, which is privately held, Obagi is public. It trades on the Nasdaq, has a nearly $357 million market cap and reported $104 million in revenue last year.

The biggest recent success story is Culver City dentist Bill Dorfman, who last month sold his 20-year-old teeth-whitening product company, Discus Dental, to Amsterdam, the Netherlands, conglomerate Royal Philips Electronics N.V. for an undisclosed amount.

Discus Dental made its name by developing teeth-whitening systems marketed as being too powerful to be used without a dentist’s supervision. The company’s product lines work by exposing a patient’s teeth to special lights after they have been coated with a patented bleaching gel that contains hydrogen peroxide.

An entrepreneurial ceramicist who built a cutting-edge business in the cosmetic dental sector is Danny Materdomini, who in the 1960s began developing what became the gold standard for porcelain dental veneers and replacement teeth.

His da Vinci Dental Studios in West Hills became a name brand outside the dental profession by lending Materdomini’s skills to cosmetic procedure-focused reality show “Extreme Makeover.” But what’s special about the company is that he continues to innovate with special bonding cements and finishings, products he also pioneered.

“A cheap veneer is like a bad hairpiece – you can see them from across the street,” he said.

Tapping market

Medical professionals are enticed to start companies for a reason: There is lots more money to be made these days as a businessman in the cosmetics field than there is as a doctor, despite the handsome earnings of top professionals.

But the field is highly competitive and especially tricky for science-based companies, which face competition from conglomerate brands like Olay and L’Oreal, which aren’t shy about touting the science behind their products in multimillion-dollar marketing campaigns.

“Consumers want to know that there are clinical studies that prove these products work,” said Karen Grant, a senior analyst with Port Washington, N.Y., research firm NPD Group. “But we saw that they’ll mix and match across channels, even going into the mass market to try products like Olay, if they believe they can get the same result.”

The smaller science-based companies also are at a disadvantage in growing their sales, since most are not distributed through cosmetics counters at department stores.

“Obagi has the challenge of trying to broaden their audience without cheapening their brand,” said Stifel Nicolaus’ Samimy. “They have to retain customers, and attract new customers who may not have had a cosmetic procedure, but they can’t start putting products on the shelves of a Sephora beauty store.”

Under investor pressure for quarterly growth, Obagi has responded by attempting to recruit physicians outside traditional cosmetic specialties to also carry its products. Among those are gynecologists.

The competition can be cutthroat. Dr. Obagi got into a nasty fight with his own company, where he remained a significant shareholder and adviser after selling it to investors who took it public in 2006. In January, he accused management of anticompetitive practices against him after he went on to found a consumer brand called ZO Skin Health.

The litigation is continuing, though the Long Beach company in September finally agreed to terminate Obagi’s consultant agreement, accelerate payments due him and no longer attempt to enforce noncompete provisions in the contract.

“Beauty in general is a tricky market to play in, because people’s views on what they’re willing to spend on a product are so broad,” Samimy said. “Then you go to a dermatology conference today, and you’re seeing hundreds of other booths touting their scientifically based products. You’re playing in a very competitive market; standing out is tough.”

Future is scientific

In the near term, perhaps the greatest challenge facing L.A.’s new crop of companies is the economy and projections of slow growth, potentially for several years.

That’s a concern for companies that sell products that are paid out of pocket and not covered by traditional medical insurance. Samimy noted that Obagi saw revenue declines in some quarters as its affluent customers became more budget conscious.

“People have to pay for these products themselves out of their discretionary income,” she said. “Companies in the space have discovered their products were more economically sensitive than they anticipated.”

However, in the longer term, science-based products are expected to become an even greater share of the global beauty and cosmetics market, which Euro Monitor estimated will grow 8.5 per cent to $85.5 billion by 2014.

And like any other business, the companies continue to break new technological ground. With cosmetics, that has meant entering the growing field of biotechnology. Locally, the best example is Kythera Biopharmaceuticals and its injectable fat dissolver. As of yet, there are no others.

Ahmed Enany, chief executive of the Southern California Biomedical Council trade group, said that few biotech startups are being formed here targeting the aesthetics market.

He noted that U.S. regulators last month rejected an application from a San Diego company to market what would have become the first new prescription weight loss drug in more than a decade. The agency said there was too much of a cancer risk.

“There have been some notable disappointments, and that can make potential investors wary,” Enany said. “There’s a lot of money to be made, but the science and technology isn’t there yet, especially for a pharmaceutical approach to obesity, which would be a huge moneymaker.”

However, Kythera Chief Executive Keith Leonard thinks the area, which is home to the world’s largest biotech, Thousand Oaks-based Amgen Inc., is in a good position to be a leader in the field.

“In addition to the biotech talent here because of our proximity to Amgen, we also have access to excellent physicians in dermatology and plastic surgery who have become advisers to our company,” he said. “We’re here for the long term.”