One look at East West Bancorp Inc.’s annual proxy statement says a lot about the size of executive paychecks in 2009.

Dominic Ng, chief executive of the Pasadena bank holding company, received $2.52 million in total company compensation last year, a sharp drop from the $4.29 million he made in 2008.

But even that doesn’t tell the story.

A surprising footnote in the filing states that Ng didn’t actually earn $4.29 million two years ago, because he never received $1.15 million in stock. That’s because the bank sustained some hits in the financial crisis, negating his performance-related stock award.

Welcome to the wild world of executive compensation.

The pay of many local executives was down last year – though sometimes it’s hard to say by how much because of accounting rules and compensation packages that included options and conditional stock grants.

But this much is clear: Boards are trying harder than ever to link executive compensation to a company’s performance amid unrelenting pressure from shareholders. Traditionally, that has meant as stock prices go, so goes pay. Today, a company’s net income and other financial metrics are playing a bigger role.

So how does it all add up?

The chief executives at Los Angeles County’s 50 largest companies got hit hard for the second consecutive year as the economy slowly pulled out of the recession. Cumulative pay dropped by $80 million – or 20 percent – to $322 million.

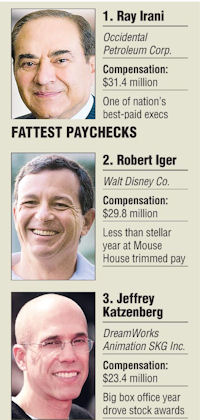

Even the top exec on the list, Occidental Petroleum Corp. Chairman and Chief Executive Ray R. Irani, saw a pay decline of 48 percent to $31.4 million. That put him ahead of Walt Disney Co. Chief Executive Robert A. Iger, whose pay was down 3 percent to $29.8 million.

Coming in at No. 3 was DreamWorks Animation SKG Inc. Chief Executive Jeffrey Katzenberg at $23.4 million. He bucked the trend, with his compensation more than doubling due to option awards and the studio’s strong performance at the box office.

All in all, nearly half of the executives took home less in total compensation.

“We are clearly seeing many more companies putting themselves through stronger rigor to determine metrics for more appropriate payout levels,” said David Insler, senior vice president in the Westwood office of Sibson Consulting, which advises companies on executive pay and other matters.

‘Performance shares’

Using publicly available data taken from companies’ Securities and Exchange Commission filings, the Business Journal analyzed the 2009 pay for the heads of the county’s 50 largest public companies, determined by market capitalization. The executives were ranked by total company compensation, which included salary, bonuses, stock and option grants, and any additional perks.

The analysis showed that as part of a refinement of the performance-based pay trend that has been popular for the last decade, companies are finding new ways to tie their executives’ compensation to the success of the firm.

In the last few years, that has led to a shift away from stock options toward so-called “performance shares” or “restricted shares,” which are stock awards often tied to metrics such as profitability, revenue or earnings per share.

Consider Irani, one of the highest-paid executives in the country. In 2009, he earned only about half of his 2008 total compensation of $60.5 million. Richard S. Kline, the company’s vice president of communications, said Irani’s pay is now “more than 92 percent at-risk and performance based.”

Among the metrics used to calculate his compensation is the company’s relative stock performance compared with its peers, as well as earnings per share. Yet the reduction of pay apparently wasn’t enough for shareholders, a majority of whom voted May 7 in a nonbinding action to not approve of the oil company’s compensation of its top executives.

Kline noted that Oxy’s board has met with institutional shareholders for years to discuss compensation and other issues. He said that in about six months the board’s compensation committee is expected to make recommendations on policy changes for compensation.

“It’s been a very open discussion. This voluntary stockholder advisory vote was simply another step in expanding dialogue with shareholders,” Kline said.

In the case of Ng, performance-based metrics meant he missed out on stock awards in 2008 when East West Bank got caught up in the collapse of the real estate market. The bank was forced to set aside $226 million to cover bad loans and took more than $300 million in federal Troubled Asset Relief Program money.

Citing its annual loss, which totaled $59 million, the board’s compensation committee did not award the $1.15 million in performance-related stock awards that Ng was in line to receive in 2008. What’s more, Ng voluntarily agreed to give up any bonus in 2009 even though the bank ended up turning a profit.

An East West spokeswoman said the compensation committee’s philosophy has been to “tie rewards to actual performance.”

The move toward performance shares began in 2007. Part of that can be traced to new accounting standards that were implemented in 2006 requiring companies to mark options as expenses, which is a hit to Wall Street-watched earnings.

“Once that happened, people said, ‘Well, stock options aren’t such a good deal anymore,’” said Paul Hodgson, senior research associate at Corporate Library, a governance research, executive compensation data and investment risk analysis firm based in Portland, Maine.

Hodgson also attributes the switch to performance shares to demands by shareholders that executives’ pay be more realistically tied to a company’s results.

“If they are properly tied to performance metrics, restricted stock is typically a better deal for shareholders,” he said.

Tinkering companies

Given the volatility in the stock market, some companies have tinkered with their executive pay plans midyear. Disney is a good example.

In the past, the Burbank media and entertainment company based performance bonuses, among other metrics, on the strength of its stock price, adjusted to reflect the value of dividends, relative to the Standard & Poor’s 500 index. But the company did away with that policy during its fiscal year ended Oct. 3, 2009, and moved to a financial metric that included earnings per share. It noted in a filing that using the dividend-adjusted stock value was a “short-term” measure while the new plan better reflected “long-term shareholder value.”

Iger took a 3 percent cut to his total company compensation in 2009 based on the new metrics. It’s unclear how he would have fared under the prior plan. Disney shares adjusted for dividends underperformed the S&P 500 by 2.4 percent during the company’s fiscal year. A Disney spokesman declined comment, referring any questions to the company’s proxy.

Fred Whittlesey, who leads the West Coast executive compensation practice of the Hay Group consultancy, said he was not surprised by corporations making changes on the fly to their compensation practices.

“A lot of companies are experimenting with different forms of pay in reaction to shareholder complaints, but it’s very difficult to set performance goals when the economy falls apart and then rebounds in a 12-month period,” he said.

Indeed, analysts said it will be quite a while before a clear picture emerges on how the changes have affected compensation.

Many companies issued large amounts of stock options and performance shares to executives when stock prices were at or near record lows in spring 2009. Whittlesey believes that will lead to “record executive compensation earned in 2010.”

But other analysts said that options and performance shares granted before the bust lost much of their value, offsetting the expected high payouts from last year’s grants.

“It is difficult to give a clear description of how it’s changed,” said Insler, the Sibson consultant.