The idea looked great on paper.

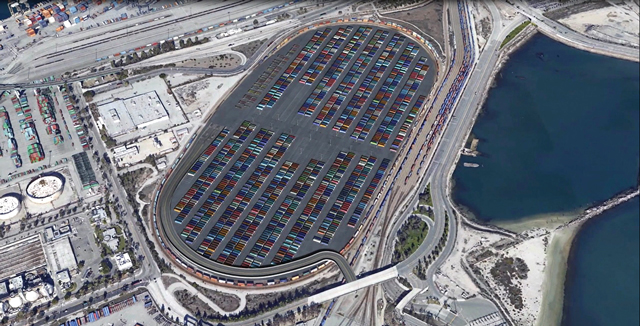

Port of Los Angeles officials said a proposed plan to turn an 80-acre former coal storage site into a staging area for cargo containers would ease mounting congestion at the docks — and bring back some of the big shippers who were increasingly sending their cargo through competing ports on the East Coast.

The man with the plan was Jonathan Rosenthal, a private equity manager and entrepreneur who’d developed a friendly rapport with port officials, infrastructure development groups and International Brotherhood of Teamsters truck drivers. Dubbed the Harbor Performance Enhancement Center, Rosenthal’s $130 million project had the public support of L.A. Port Executive Director Gene Seroka as well as investment from Australia’s Macquarie Group, one of the world’s largest infrastructure investment firms.

But in May, after three and a half years of working together to develop the site, Seroka told Rosenthal the project was off in a formal memo on port letterhead. “The Port of Los Angeles (‘POLA’) has determined the proposed project to be infeasible and provides notice of termination,” the memo read.

Rosenthal wasn’t happy. “At the port’s encouragement, we’ve spent millions of dollars to begin the environmental permitting process and launch a one-year pilot program, fully approved and permitted by the port,” Rosenthal said.

Officials have cited environmental criteria as reasons for terminating the project, and they’ve said HPEC lacked a viable operational and financial plan.

But what likely stalled the port’s yearslong attempt to improve its operation is the very mechanism that keeps the port running day in and day out: the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, which represents thousands of dockworkers across the West Coast ports.

Privately, port officials often worry that any disagreement with the dockworkers could slow cargo movement and hurt the port’s reputation among global shippers.

“Labor matters a lot, and they have incredible power,” said Paul Bingham, director of transportation consulting at London-based IHS Markit Ltd. “I am not surprised at all this happened. If it was easy (to develop at the port), there would be a lot more near-dock facilities operating.”

Behind the scenes

The dockworker’s union had sought exclusive rights to provide trucking services for the project — an arrangement Rosenthal said he wasn’t sure HPEC could afford.

Technically, the off-dock facility sits outside the jurisdiction of the ILWU, which covers workers employed by port terminal operators.

But Rosenthal said he was open to creating other nontrucking jobs for ILWU workers at the site. In a letter to ILWU President William Adams in February, Rosenthal offered to work with an ILWU employer to run HPEC’s container yard. But Rosenthal said his efforts to work with the union were rebuffed.

ILWU officials involved in the talks didn’t respond to requests for comment. One official who wasn’t involved the talks said it was hard to understand why the union wouldn’t sign on. “It’s a head scratcher for me, especially if it was going to create more work,” said Paul Trani, an ILWU Local 63 board member.

Rosenthal’s relationship with the Teamsters complicated the issue. In early plans, HPEC had proposed hiring a trucking company, Total Transportation Services Inc., backed by Rosenthal’s private equity firm, Saybrook Capital, to serve as the main operator. The drivers at Total Transportation are part of Teamsters Local 848.

Eric Tate, secretary-treasurer of Teamsters Local 848, said that proposal put the two unions at odds.

“They cost additional jobs that we could have got as well as additional jobs for themselves,” he said of the ILWU. “Their narrow look at this situation has put them in a position where they are losing jobs when they could have gained jobs.”

For the ILWU, the potential loss of jobs is a particularly sore subject at a time when automation is on the rise at the port.

Last month, ILWU protests over automated equipment at one port terminal roiled several meetings of the Los Angeles Board of Harbor Commissioners. In the end, the nation’s largest terminal operator reached an agreement to retrain dockworkers after months of raucous protests, but the objections of the union drove a wedge between the port, city officials and some of the largest terminal operators.

HPEC’s failure to nail down an agreement with the powerful ILWU was likely its downfall.

In April, a month before officially terminating the project, Seroka sent Rosenthal a text message warning that the project could fail without the dockworkers’ support. “Any way it is sliced, they run the port and will put up a fight every step of the way,” he wrote.

A new battle

Rosenthal has taken the port to court.

In a complaint filed last month in L.A. Superior Court against the City of Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Harbor Department and the Board of Harbor Commissioners, Rosenthal asked the court to overturn the port’s decision.

Rosenthal’s lawyers argued Seroka’s termination violated the city charter because it wasn’t authorized by the City Council or the Board of Harbor Commissioners.

The city responded, saying the contracts signed with HPEC are invalid because some of them expired before being officially ratified. Moreover, the city said as HPEC’s plans evolved, they didn’t include “clean” or low-emission trucks — a requirement at the port — nor did the company have a viable financial plan.

Rosenthal denies both assertions, adding that the port’s rules would have mandated cleaner burning trucks — and HPEC would have followed them.

City officials said in court filings that they’ve moved on, aiming to utilize the site for “better purposes.” Ultimately, they argued, HPEC failed to “resolve the labor component.”