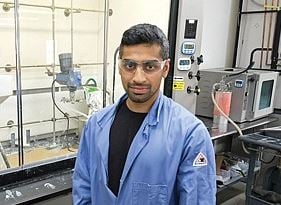

Akshay “Shay” Sethi was an undergraduate student at UC Davis researching extremophile bacteria – tiny organisms that live in extreme environments – when it dawned on him that the chemicals inside these lifeforms could be a solution to the world’s plastic pollution crisis.

Four years, $2 million in funding and hundreds of research hours later, he’s come up with an inexpensive chemical formula that can break down one of the most ubiquitous plastics: polyester.

Sethi hopes the process – and his company, Ambercycle Inc. – revolutionizes the $316 billion fast-fashion apparel industry by offering a cheap, simple way to turn discarded garments destined for landfills into brand new clothes.

If Ambercycle, which was founded in 2015 and does business as Moral Fiber, can deliver, it would be a boon for retailers and apparel-makers struggling to address growing demand from consumers, policymakers and the industry itself to clean up the waste they create.

“We will be the only clothes (manufacturer) in the world to do everything under one tent, to take the raw material and go all the way to the finished product,” Sethi said.

The idea of recycling fabrics used in apparel is known in the industry as closing the loop, and it’s been the buzz of “woke” clothing manufacturers for years as they try to reabsorb the waste they produce.

And there’s a lot of it.

The American Apparel & Footwear Association estimates that Americans consume about 66 pieces of clothing a year. Much of that ends up in landfills − about 10.5 million tons of textiles, according to the most recent figures from the Environmental Protection Agency.

Local apparel-makers, such as downtown-based Guess Inc. and Lucky Brand, are searching for alternative solutions.

“There are a lot of manufacturers out there looking for an option,” said Allison Charalambous, social compliance manager at Lucky Brand.

The label best known for jeans and its California casual style has, like other brands, been grappling with how to deal with the stream of toss-away material created during production. The two main options are to break down fabrics or send bales of scraps and clothes to secondary markets in foreign countries. The latter option might have a limited window of viability, however, with China and some countries in Africa attempting to block the stampede of clothes.

“I have reached out to other sustainability managers,” Charalambous said. “They don’t have a solution.”

Polyester problem

Fashion brands that have recycling programs, such as Guess, rely on products being either reused as second-hand clothing or shredded and repurposed for rags or couch stuffing. Clothes’ lifetime may be extended by the process, but it doesn’t fix the core problem because these products ultimately end up in the dump as well.

Polyester fabrics are particularly difficult to recycle because, unlike cotton, there hasn’t been a method to break down the material easily or cheaply.

Moral Fiber’s technology offers a solution.

Using chemicals that are mixed in custom-built sealed reactor, the company can turn an old polyester-blend dress into polyester resin pellets in 30 minutes. Those pellets can then be spun into polyester thread for new garments.

Sethi was struck by the idea for the polyester recycling program a few years ago when he was researching how plastics can be broken down to a molecular level. A recycling industry contact put him in touch in 2016 with Swedish clothing giant Hennes & Mauritz AB (H&M), which asked if the technology could work on clothes. Sethi said yes, and weeks later, he was awarded a $300,000 grant from the company that jumpstarted his business.

“This was life changing because we had never seen that much money,” Sethi said of the grant. “We didn’t know what the technology was going to be used for. We weren’t really in it to make a business.”

Angel investors and a grant from the National Science Foundation have further buoyed the company’s total funding to $2 million.

The money allowed Sethi and his business partner Moby Ahmed, who are 25 and 24 years old, respectively, to open two months ago a 10,000-square-foot factory in Boyle Heights, close to the region’s apparel manufacturing hub.

Sethi said Moral Fiber is in talks with recyclers, clothing manufacturers and investors to see how its process can be used and grown.

“Right now, we are just figuring it out and doing the necessary R&D,” he said.

The technology is nimble enough, Sethi claims, to be showcased in stores, which offers the added bonus of making transparent what is an opaque, global recycling market. Some manufacturers have expressed interest in breaking down clothes and creating new ones under their own label. In July, when Moral Fiber has its Boyle Heights plant fully running, he expects to raise a Series A funding round.

Welcome development

Charalambous, Lucky Brand’s social compliance manager, said she’s already in talks with Moral Fiber. In the eight months she’s been examining sustainability issues for Lucky, she’s collected a 4-foot-by-4-foot pile of unusable scraps – now waist-high – that she wants the company to test its recycling process on.

Designers, fashionistas and other industry insiders said Moral Fiber’s recycling program is exactly the kind of innovative business that’s missing from their industry.

“This is a really big deal. (Polyester) blends have been very difficult,” said Jennifer Gilbert, the Los Angeles-based chief marketing officer for I:Collect, a German company that collects textile waste for retailers like H&M and Guess.

Next month, the United Nations will launch an alliance with fashion industry heavyweights committing to reduce their environmental damage. The international body blames an increasing amount of ocean plastic waste on the $2.5 trillion dollar global garment industry.

“In some ways, this is a moral imperative for the industry,” said Nate Herman, the American Apparel & Footwear Association’s supply chain guru. “Consumers are interested in knowing that the product that they are buying has sustainability.”

Herman, whose association represents some of the biggest names in clothing from North Face Inc. to Target Corp., said retailers across the slate are hard at work trying to cut down on their waste and develop greener lines.

“We need to find a way to make recycling and reuse work to address the end of our supply chain,” he said. “This could help move the industry forward.”