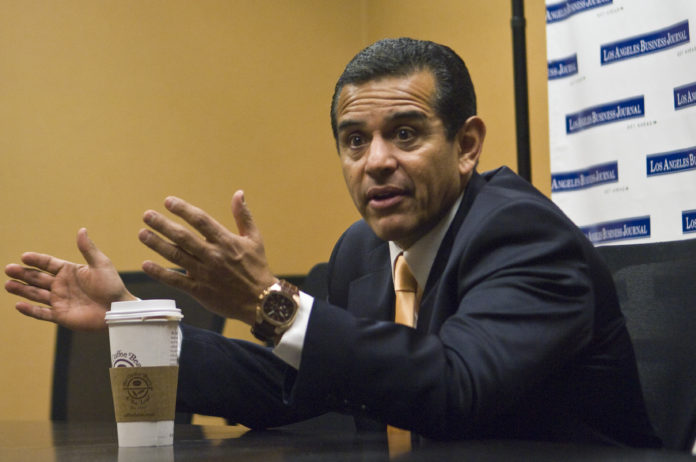

To the delight of local business groups, Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa last week said he wants to kill the city’s high and much despised gross receipts business tax.

The mayor’s change of stance – he has in the past only favored reducing the gross receipts tax and granting some exemptions to it – makes it likely that a measure to kill the tax will go to the council and face a good chance of adoption.

“I do favor elimination of the gross receipts tax,” Villaraigosa told the Business Journal. “We have to create a smarter, more efficient tax structure.”

The mayor’s shift comes as a committee is about to recommend business tax reform to the City Council. A key factor in the recommendations is a finding in a report that shows that previous business tax reductions have led to increased city revenue because more businesses formed and stayed in the city. The report projected more city revenue and job creation if the gross receipts tax were reduced or killed.

The committee, led by local investment banker Lloyd Greif, is scheduled to make its recommendations to the City Council next week, and is expected to call for major reductions or elimination of the tax for most businesses in the city.

The gross receipts tax brings in an estimated $425 million annually, about 10 percent of the city’s general fund budget. If that tax is eliminated and more businesses start up and stay in the city as a result, the city will get increased revenue from utility, property and sales taxes, according to the draft report.

Business leaders and elected officials agree that the tax would be eliminated in stages, allowing the city to avoid a sudden steep revenue loss.

Businesses have long complained that the highest tax rates are five to 10 times the tax levels of other nearby cities and push companies to leave or expand outside the city. Seven years ago, the city enacted a 15 percent reduction in the business tax. Business groups said it did not go far enough.

Villaraigosa’s predecessors, Richard Riordan and James Hahn, each favored reductions in the business tax or exemptions for certain types of companies, such as new or small businesses.

Villaraigosa signaled his shift in a speech to the Valley Industry and Commerce Association. VICA, a Sherman Oaks non-profit that promotes area business interests, has for years called for axing the business tax.

“When he jumped on eliminating the business tax, I looked around the room and people’s mouths dropped open,” said VICA Chief Executive Stuart Waldman. “We asked ourselves, ‘Did he really say what we think we heard him say? Yes, he really did.’”

City Council President Eric Garcetti has said he is open to the idea of killing the gross receipts tax. So with Villaraigosa’s support, the idea may take hold.

“Los Angeles cannot continue to be the most expensive city in the region when it comes to business taxes,” Garcetti told the Business Journal last week.

Local business leaders greeted the prospect enthusiastically.

“We’re very excited,” Waldman said. “Having the mayor on board means that something is going to get done and Los Angeles will finally be in the game when it comes to attracting and retaining businesses.”

Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce Chief Executive Gary Toebben said that if a time line is established for eliminating the tax, business investment in the city will pick up.

“Elimination of the business tax would be a strong statement of support for business growth and investment,” Toebben said.

L.A.’s gross receipts tax has nine brackets. The lowest rate, $1.01 for each $1,000 in receipts, applies to telephone and multimedia companies. The highest, at $5.07 for each $1,000 in receipts, applies to law firms and other professional service companies.

Los Angeles has the highest business tax rates in Los Angeles County. Only Santa Monica comes close, with its highest bracket at $5.03 for each $1,000 in gross receipts. Culver City’s highest rate is $3 for each $1,000 in receipts; all other county cities with gross receipts taxes charge less than $2 in their highest brackets. Several cities – including Long Beach, Burbank and Torrance – base their business taxes on the number of employees the company has in the city. Several other cities, such as Calabasas and Glendale, don’t have any business taxes.

Reform options

Killing the tax won’t be easy. Budget hawk council members, particularly Bernard Parks, have been reluctant to support past business tax reductions because of the immediate loss in revenues to the city amid continued projected deficits.

But supporters of business tax reductions say the draft report shows that killing the tax will bring in more revenue. City officials had ordered the report months ago to analyze reform options put forward earlier this year by the city-appointed Business Tax Advisory Committee.

The draft report was prepared by Charles Swenson, a professor at USC’s Marshall School of Business. Swenson concludes that previous business tax cuts resulted in companies expanding operations in the city. That in turn led to increased revenues from sales, utility and property taxes.

The report also concludes that reducing the rates of the highest business tax categories could generate tens of thousands of additional jobs in the city and bring in up to $100 million in net new revenues over time.

Scrapping the gross receipts tax for most businesses would eliminate $380 million in annual business tax revenue to the city. But it could later generate up to $640 million in revenue from other tax sources as businesses expand or locate in the city, the report says.

The draft report analyzed options that the panel proposed, including deep cuts to the highest categories, across-the-board cuts, more exemptions, and tax relief for new business and job creation.

But the most radical reform proposal calls for simply eliminating the gross receipts tax entirely for the vast majority of businesses in the city. Greif said the tax rates are inherently unfair because the city has kept manufacturing taxes low and has pushed companies in newer industries into higher classifications.

“There’s a built-in incentive for the city to push companies into the highest tax categories possible,” he said.

The gross receipts tax has been the subject of controversy in recent years because the city reclassified many Internet businesses into the highest bracket. Some fought the higher rates and eventually got a lower classification, but at least one company – LegalZoom.com Inc., an Internet legal documents company – moved to Glendale and expanded in Texas.

Vote expected

Greif said committee members will meet Aug. 3, and are scheduled to send proposals to the City Council and Villaraigosa.

Business and economic development consultant Larry Kosmont said that the city would achieve the biggest bang for the buck by reducing the tax rates of the top four categories, which range from storage companies to professional services companies. Kosmont compares tax rates of hundreds of cities across the nation as part of an annual Cost of Doing Business Survey he co-authors.

“These four categories are where most of the fast-growing service businesses are,” Kosmont said. “Just getting these categories more in line with other cities would go a long way towards making Los Angeles more competitive.”

But Kosmont said the current gross receipts tax system is riddled with inequities and requires constant auditing to ensure compliance. A simpler system based on employee counts that’s used in many other cities in the county would benefit both employers and the city of Los Angeles, he said.

However, any entirely new system for business taxes would be sure to generate winners and losers, likely resulting in fierce fights.

“It may be at the end of the day, the city decides to keep the business tax, but at sharply reduced levels,” Toebben said. “Whatever the case, what we’ve seen with the announcements of the last week is a significant shifting of the goal posts, and that’s being welcomed in the business community.”