Aerospace Corp. has set out to establish an industry standard to help companies that launch rockets into space measure and fit small satellites in unfilled portions of cargo holds.

The El Segundo-based think tank’s efforts to develop the standard – dubbed Launch Units – was announced last week as a response to increased demand for rides to space from small satellite manufacturers. The growing demand suggests that excess capacity aboard rockets already slinging larger satellites into space could be offered on a market basis.

Aerospace Corp. plans to unveil the specifications of the Launch Unit standard during the 32nd Annual Small Satellite Conference in Logan, Utah in August.

Industry observers generally agree that standardization presents an opportunity to create defined parameters for adding secondary payloads aboard rockets launched by companies such as Space Exploration Technologies Corp. of Hawthorne or United Launch Alliance of Centennial, Colo.

There are no definitive studies on the industry’s total excess capacity, but recent examples indicate that “vehicles have launched with thousands of kilograms of excess capacity,” said Phil Smith, space analyst with Bryce Tech in Alexandria, Va. “You really want to limit the amount of wasted mass.”

The initiative echoes the invention of steel cargo shipping containers – dubbed twenty-foot equivalent units or TEUs, a name they retained even after a switch to 40-foot containers – which revolutionized the logistics industry in the second half of the 20th Century in part by establishing a clear point of reference on capacity.

Standardizing space cargo could be more complex due to various technical aspects inherent in space travel.

Moves to create standard space cargo by Aerospace Corp. come as small satellite manufacturing has exploded over the past five years. The bulk of the demand is driven by attempts to build and launch new satellite constellations – hundreds or thousands of small satellites that do the work of larger satellites by spreading out tasks. Operators include Earth imaging company Planet Labs Inc. of San Francisco and internet broadband service Oneweb in London.

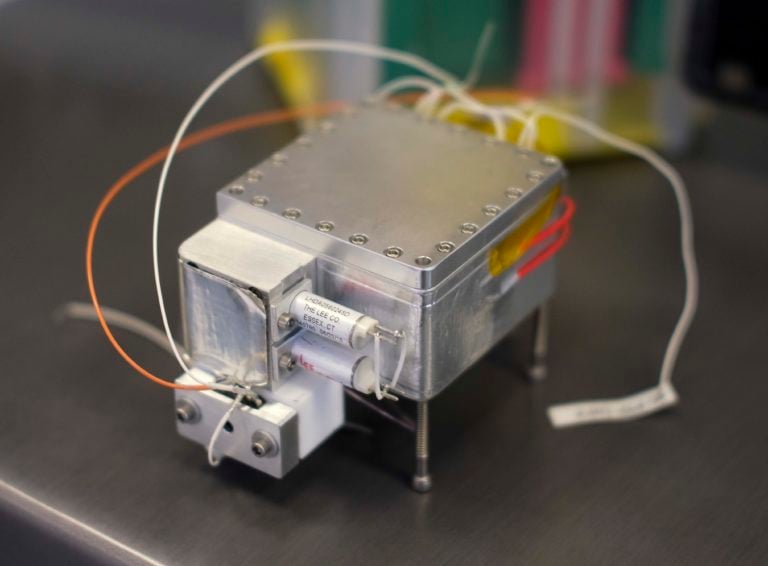

Further demand is coming from increasingly sophisticated CubeSats, which are 10-by-10-centimeter satellites – about four square inches. The CubeSats are relatively inexpensive to build and bolt together, and have put space operations in reach of everyone from academics to startups.

More than 6,200 small satellites – any that are less than 500 kilograms, about 1,100 pounds – are expected to be launched over the next ten years, according to a report by space consultancy Euroconsult in Paris. The total market value of these small satellites could reach $30.1 billion in the next 10 years, up from $8.9 billion over the previous decade.

“We have this situation where we have all these new players with all these great ideas for small satellites, but we don’t have the launch services to match them,” said Michael Swartwout, department chair of aerospace and mechanical engineering at Saint Louis University, who tracks small satellite launches. “The existing companies need to figure out how to fit more spacecraft on their launches.”

Rideshare

Manufacturers of small satellites eager to hitchhike their way into outer space at a discount have in recent years custom designed their instruments to fit into unused room aboard rockets dedicated to larger satellites.

“We are seeing the big guys, ULA and SpaceX, take on more secondary (payloads) because they realize that’s the way you offset the cost of the rocket,” said Mike Lewis, chief technology officer of NanoRacks, a service which deploys small satellites from the International Space Station as well as from a secondary payload attachment on Orbital ATK Inc.’s Cygnus spacecraft.

The larger satellite manufacturers who pay for the lion’s share of rocket launches aren’t always eager to share their rides, however, he said.

“You don’t want your little dinky (satellite) busting a $100 million spacecraft,” said Lewis. “You don’t want your hood ornament cracking the windshield of your (Lamborghini) Murcielago.”

A drawback for small satellite manufacturers who want to rideshare aboard a rocket trip: Having to build around the main payload’s needs and follow its launch schedule. Should a small satellite manufacturer want change rocket flights due to the discovery of some malfunction, the company’s engineers typically would have to redesign some of the hardware to fit its new launch mission.

“You have the opportunity to get to space, but it is through a very custom-business model – it delays your time to space,” said Randy Villahermosa, executive director of innovation with Aerospace Corp.’s iLab, an in-house incubator. “While it is certainly possible to do it today, we envision the standard will make it much easier.”

Standard configuration

Aerospace Corp. believes that the ability to swap satellites within predefined configurations will provide more launch options for satellite manufacturers and shortened lead times for integrating with rockets. Those factors, the thinking goes, will eventually lower the costs to deliver payloads to orbit.

“There is a significant increase in the small (satellite) market and yet the opportunities to launch still remain a challenge,” said Villahermosa. “(The standards are) designed to make it easier for the developers of small satellites to find launch opportunities.”

The organization wants to define an emerging category of satellites – craft that weigh approximately 50 kilograms to 60 kilograms, somewhere between 100 pounds and150 pounds or so, according to Carrie O’Quinn, senior project engineer for Aerospace Corp.

The non-profit is working on volume and mass measurements, mechanical and electric connections, and criteria for the frequency at which satellites vibrate. All of those factors hold the potential to cause serious damage.

The think tank believes it can best guide the industry’s discussions of standards because of its role as a federally funded research and development center for space-related matters of national security. It has joined with industry players to help develop the standards, including launch service providers Virgin Orbit in Long Beach and United Launch Alliance in Centennial, Colo.; small satellite manufacturer Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems Inc. of Irvine; and rideshare broker Spaceflight Industries of Seattle.