Since 2001, LegalZoom.com has sold customized legal documents online to people who want to do anything from forming a business, to writing a will, to getting a divorce – without going to the trouble, or cost, of hiring a lawyer.

The Hollywood company has been a success, growing from a startup run out of a Wilshire Boulevard condo to an operation of nearly 400 employees doing business in all 50 states.

Along the way, there have been grumblings by some in the legal profession that LegalZoom is unfairly moving in on their territory. Now, a pair of legal challenges is questioning whether LegalZoom’s business model is even lawful.

Class-action lawsuits in Los Angeles and Missouri have been filed that accuse the company of offering legal services without a license. The company had faced questions about its business model before, but had never been sued over it. The firm’s increasing visibility seems to be making it more of a target.

“I’m not certain why all these lawsuits have been brought in this time frame, but I would have to say the company is (increasingly) a recognized name brand when it comes to delivery of legal services by a nonlawyer, and that could be a factor,” said Chas Rampenthal, LegalZoom’s general counsel and vice president of product development, who denied the allegations.

The legal challenges come amid recently announced plans to open an expansion office in Austin, Texas, that would potentially house hundreds of employees. Those plans have not been curtailed by the lawsuits.

Gillian Hadfield, a law and economics professor at USC who studies legal markets, said the suits are a sign that the growing company is ruffling feathers.

“I would not take it as an indicator that they’re doing bad stuff,” Hadfield said. “I’d take it as an indicator that they’re challenging the status quo.”

Consumers who go to LegalZoom’s website can fill out customizable legal forms online that are checked for errors by customer service employees who make follow-up phone calls as needed. The package for incorporating a business, for example, can cost as little as $139. In comparison, “a lawyer would charge you approximately $1,480 for the standard incorporation package,” the website states.

The Los Angeles Superior Court lawsuit, filed May 27, alleges that LegalZoom misleads consumers by advertising its services as “attorney-quality” and seeks “an order prohibiting defendants from engaging in the unauthorized practice of law.” The case was filed on behalf of a San Francisco woman named Katherine Webster, who claims she bought a living trust on behalf of her uncle that turned out to be so problematic she had to hire an attorney to fix it.

The Missouri case, filed earlier this year, also seeks to bar LegalZoom from “unlawful practice” of the law in that state, and cites a cease-and-desist letter sent by the North Carolina Bar to LegalZoom. Despite the cease-and-desist order, Rampenthal said LegalZoom continues to operate in North Carolina.

The lawsuits, though, pose a serious challenge to LegalZoom, because a loss in either California or Missouri could invalidate its business model there and open it up to similar challenges in other states, said Bernard Resser, an attorney at Century City-based Rutter Hobbs & Davidoff and who is experienced in class-action cases and unfair competition. But a victory could also further legitimize the business moving forward.

“Their entire business is threatened if it’s deemed unlawful practice of the law,” Resser said. “If they overcome the injunction, that certainly clears the way for their operations and continued success.”

Success story

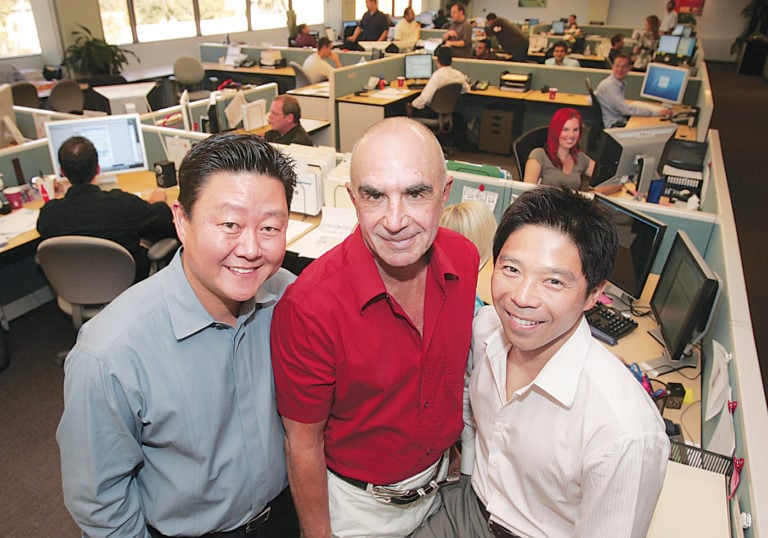

LegalZoom is a classic success story that has been well documented. Attorneys Brian Liu and Brian Lee quit their jobs at high-profile law firms, teamed with Web developer Eddie Hartman, and turned to friends and family for $250,000 in seed money to launch the company out of Lee’s condo in 2000.

They were able to bring in Robert Shapiro, the former O.J. Simpson lawyer who has become the public face of the company, as a majority shareholder after pitching him the idea on a cold call.

The website went live in 2001 while the founders were still in the condo. About 2003, the company moved out of a 900-square-foot office on Larchmont Boulevard to its current headquarters on Hollywood Boulevard, where its 400 employees are spread across five floors of a building.

LegalZoom, which began running television and radio commercials starring Shapiro more than three years ago, claims it’s served more than 1 million customers.

LegalZoom is “still evaluating our options” regarding a possible move out of the city of Los Angeles to avoid a new higher tax rate, spokesman Scott MacDonnell said.

The company succeeded, Hadfield believes, because it was able to fill an important gap in the legal marketplace for affordable services.

But Tim Van Ronzelen, an attorney at one of five law firms representing plaintiffs in the Missouri case, said that LegalZoom violates Missouri law, which has a statute barring legal document preparation by nonlawyers.

“What LegalZoom does in Missouri is they charge money for preparation of legal documents without having a legal license,” he said.

The law governing how much assistance can be provided by nonlawyers in the preparation of legal documents varies state by state but generally bars any kind of advice, Hadfield said.

So for example, in California, “legal document assistants” who meet a minimum level of experience or education and are registered in their counties are allowed to help customers prepare documents. That includes helping people understand the form but prohibits them from helping fill it in. They also cannot tell clients what forms they might need or what might be the legal effect of a filing.

Consumers can opt for self-help books or software that provides documents that are similar to a legal version of TurboTax. But even those types of services have had their own legal battles.

Nolo Press, a Berkeley publisher that publishes books of legal forms, famously fought off a number of legal challenges, and even had to get a state law passed in Texas in the 1990s to protect it and similar business from accusations of practicing law without a license.

“There’s a huge gap in what the market’s able to provide to help people to navigate the legal world,” said Hadfield, who supports more affordable services and does not believe the L.A. case has merit.

“We should make it easier for companies like LegalZoom to operate in a way that’s fairly priced and sufficiently protective of consumers’ interests, not harder,” she said.

No ‘bright line’

The L.A. case has a long way to go. LegalZoom has not yet filed a response to the recent lawsuit, and it can sometimes take well over a year to have a case certified for class-action status.

The status is only given when a plaintiff can show enough of a common link with multiple other plaintiffs who would benefit from a combined single lawsuit. Such status also encourages law firms to handle complaints that otherwise might not be financially worthwhile to pursue.

Resser said the plaintiffs’ attorneys may face trouble in getting certified as a class-action case.

That’s because the L.A. case primarily argues that LegalZoom’s alleged misrepresentations of itself as “attorney-level” led their client to purchase a bad living trust. But it sues on behalf of anyone in the state who’s purchased a living trust or will, regardless of whether they were duped by LegalZoom’s alleged misrepresentations or whether their product ended up being problematic.

“They may end up with a class where the majority of class members may not have a claim,” Resser said. “I think there’ll be a big fight over whether this deserves class certification.”

The Missouri case, which sues on behalf of everyone in that state who has used the service, has yet to receive class-action certification as well. A judge recently denied a motion by LegalZoom’s attorneys to move that case to California, leaving the company until June 16 to file an answer or another motion.

Both sides in each case could potentially have good arguments.

“Once you tell someone, ‘Oh, you’ve entered everything correctly and this is legally enforceable,’ that seems like it could be legal advice,” Resser said. “But it isn’t a bright line.”