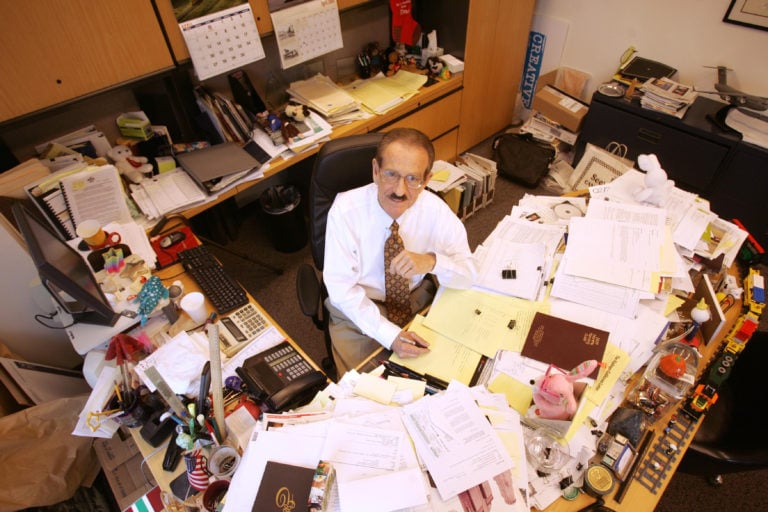

Jack Kyser has been dubbed the guru of the L.A. economy. For most of the past quarter-century, he’s been the go-to person for the media, business leaders, and elected officials who need information and analysis about local economic issues. Besides issuing regional forecasts several times each year as the head economist for the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corp., he’s always ready to chat about interesting tidbits about the local economy. Kyser, who turned 75 in April, has handed over the title of chief economist to colleague Nancy Sidhu. Kyser has taken the title of founding economist and will continue studying the L.A. landscape. The Business Journal sat down with Kyser at his downtown office with its view of the U.S. Bank Tower to discuss this transition, the art of forecasting and the local economy.

Question: What was the Los Angeles of your childhood like?

Answer: I was born in Huntington Park, but very early on my family moved to Downey, close to where my adopted father was working in a Studebaker plant. One of my first memories was of having to take shelter one night during the war because we all heard that the Japanese were coming to bomb Los Angeles. It turned out to be a false alarm, but everyone was really scared.

Q: You mentioned your adopted father. Who was your biological father?

A: I don’t really know too much about him. His last name was Salas, so if he and my mother had remained together, I would have been Jack Salas, not Jack Kyser. But shortly after I was born, my parents split up and I never saw or heard about my father again. The little I know about him came from my grandmother once my mother was through with someone, that was it. I don’t even know why my father and mother split up. Meanwhile, my mother found a job as an administrative assistant at this Studebaker plant in the Long Beach area, where she met Mr. Kyser. They married and he adopted me.

Q: How did you decide to become an economist?

A: I sort of fell into it. I was an industrial design major. I applied for a draftsman post at Security First National Bank and was put to work drawing charts to accompany monthly summaries of economic conditions for bank officials to use in presentations. Remember, at this time there were no computers, so charts had to be plotted and drawn by hand. Over time, I found the subject matter of those charts much more interesting than drawing them up, so I decided I wanted to go into economic research.

Q: Did that mean you had to go back to school?

A: Yes. I went back to USC to get an M.B.A. And what was really good was that the bank helped pay my way. After I received my M.B.A., I went to work for United California Bank in their economic research department.

Q: Why didn’t you stay there?

A: I answered a blind ad in the Wall Street Journal for an economist position at a “Midwest transportation company.” It turned out to be Union Pacific Railroad. They flew me out to their offices in Omaha, (Neb.), for an interview and offered me the job. My friends out here thought I was crazy to accept; that as an L.A. native, I wouldn’t last through one winter in Omaha. It turns out, my friends were almost right, but not for the reasons they thought.

Q: What happened?

A: Well, I accepted the job in 1980 and for a while things were really good. I made a lot of friends. I even became friendly with Marlin Perkins for those who remember the “Wild Kingdom” television series, he was the host. Then, the recession hit and thanks to some internal politics and the impacts of that recession, I got laid off. I found myself stuck in the middle of the country in the middle of the worst recession since World War II. I thought no one was going to hire me and certainly no one was going to pay to move me to another location.

Q: Did you actually put out forecasts when you were at Union Pacific?

A: No. I worked on internal economic reports. In the goods movement business, having a good grasp of where the economy is going is absolutely essential.

Q: So what did you do after you were laid off?

A: I started doing some volunteer fundraising work for the local National Public Radio station, KVNO. Mainly I was looking for anything to do so I wouldn’t go crazy. The next thing I knew, they were asking me to do business reporting for a new local version of “All Things Considered” they were starting. That was a very interesting experience and a turning point of sorts. There I was selling sponsorships in the morning and doing radio broadcasting with no prior experience in the afternoon. It was a really quirky station.

Q: What did you learn from that experience?

A: I learned a valuable lesson that you must always cultivate good relations with the media. I learned the importance of always calling reporters back, which is a lesson I’m still practicing today.

Q: Why did you come back to Los Angeles?

A: The radio station gig wasn’t a lot of money, but it allowed me to buy some time so I could sell my townhouse and move back to Los Angeles. So I ended up spending three winters out there in Omaha before I returned to California. When I crossed the border into California, I vowed I would never leave the state again.

Q: What happened then?

A: The L.A. chamber’s longtime economist, Jimmy Lewis, had just passed away and they were looking for a replacement. I was available, so I applied and got the job. And the timing was really fortuitous for my career, because you had the Olympics set for the following year.

Q: How was that fortuitous?

A: Everyone was predicting the Olympics would be a disaster: The Russians were boycotting, the traffic would be an absolute nightmare and the Games were going to lose oodles of money. We at the chamber were supposed to be the boosters for L.A. and the media were all over us. But I took one look at the level of civic engagement and the energy that was building here and the business model that the Olympic Committee followed and I predicted that the Olympics were going to be fine. That turned out to be my first good call as an economic forecaster: As we all know, that turned out to be one of the most successful Olympics ever.

Q: What prompted you to join the LAEDC?

A: In late 1990, as that recession was just starting to take hold, the LAEDC board decided to concentrate more on economic development. They brought in this respected economic development official from Cleveland, Gary Conley. He met with me and asked me to join his organization in a newly created post of chief economist. So I signed on. My job was to know the L.A. economy better than anybody else so that the LAEDC could then do its job on economic development.

Q: With the economy tanking, that must have been a tough assignment.

A: It was difficult and it was also sad. I would go out and talk to these laid-off aerospace workers and they really didn’t know what they were going to do. They had been working in aerospace firms for most of their lives and now they really had to struggle to rebuild their lives. I put out my first forecast for the LAEDC in 1992 and it made for very depressing reading.

Q: What was the most interesting part of doing these early forecasts?

A: In 1992, we had the riots. And in 1994, we had the earthquake. In each case, I would get these calls from media outlets all over the world, and they would say, “Well that’s the end of L.A., isn’t it?” People really had this skewed idea of L.A. that the whole place was imploding.

Q: What perspective do you bring to your forecasts?

A: I make sure to have a global focus. One of the great traps for local economists is just to be focused on what’s going on in your industry or your neighborhood to have a very narrow focus. I realized that you constantly must have your radar up for what key issues around the country and around the globe can impact you.

Q: Have you been accused of being an L.A. booster?

A: Yes, sometimes. But what you try to do is to be very, very honest about your forecasts. Tell people what’s really going on, what you really think is going to happen.

Q: Have you ever been pressured to tailor your forecasts to suit the larger goals of the LAEDC?

A: No. I have never run into that pressure here.

Q: What’s been your biggest missed call as a forecaster?

A: If by that you mean a forecast that’s totally missed the boat, there really hasn’t been one. For instance, we did forecast a year ago that we would go into recession and that really set off alarm bells. Remember, most people were saying we were going to skirt by without going into recession. Having said that, there have been forecasts where we didn’t get the magnitude of certain trends right.

Q: Why?

A: Well, there are gaps in the data and then there are constant revisions. So sometimes the data you feed into the forecast model aren’t correct, so you do miss some things.

Q: What’s been the most difficult forecast?

A: I’d have to say the most difficult was right after 9/11. There were so many uncertainties: Would there be another terrorist attack? When would things calm down enough so people could start flying again? There was no way to put any of that into an economic model. After that, I’d say the next most difficult forecast was the one we just did in February. This recession is hitting so many industries in that way it’s unlike recent recessions.

Q: Why did you change your title from chief economist to founding economist?

A: I’ve had some health problems recently. I’ve been hospitalized a few times and was basically told that I needed to scale back my work activities. I had been doing three or four presentations a week, along with all the forecast work and economic development activities. So I went to Bill Allen, LAEDC’s chief executive, late last year and told him that I could not maintain this kind of schedule. That’s when the decision was made to hand over the chief economist title to Nancy Sidhu.

Q: What kind of health problems have you had?

A: There have been several, actually, and they’ve all come together at once. It’s like I’ve been hit by a bus. It started in April 2007, when I broke my left kneecap in a fall. Four months later, I was in physical therapy to try to get that leg back into shape when I became faint, fell and broke my right leg. As if that wasn’t enough, last September, I had problems with my kidneys and landed in the hospital for two weeks. I’ve been battling back since then; now I’m only working about 30 hours a week.

Q: What’s been the most frustrating part about all this?

A: Besides not being able to work as much as I used to, it’s the special diet I’ve been put on. No chocolate and I just love chocolate. Also, no tomatoes, no cheese, no bacon, no sausage. People have been telling me I’ve lost so much weight. Well I tell them, “How am I supposed to gain weight on a diet like I’ve been put on?” But through all this, I still enjoy economics and I’m really grateful that I’ve been allowed to continue my work.

Q: You now have a bit more time outside of work. What are you doing to fill that time?

A: One thing I’m doing is catching up on reading mystery novels, which is something I really enjoy. I love to travel, but with everything that’s been going on with my health, that hasn’t really been an option. I hope I can do some more traveling sometime soon.

Q: Where would you like to go?

A: I would love to go back to Chicago and New York. There’s so much to do in each of those cities so many shows to go see.

JACK KYSER

TITLE: Founding Economist

ORGANIZATION: Jack Kyser Center for Economic Research at the Los Angeles Economic Development Corp.

BORN: 1934; Huntington Park

EDUCATION: B.S., industrial design, 1955; M.B.A., 1968; both from USC

CAREER TURNING POINTS: Taking post as economist with Union Pacific Railroad in Omaha, Neb.; after layoff, working as business reporter at local NPR station; returning to Los Angeles and joining L.A. chamber as economist

MOST INFLUENTIAL PEOPLE: Conrad Jameson, economist 50 years ago at Security First National Bank; Don Conlon, economist with Capital Research; Gary Conley, former president of LAEDC

PERSONAL: Lives in Downey; single, one cat

HOBBIES: Collecting plein air paintings; reading mystery novels